<< Go Back up to Theatre Research

New visitor? Read more about Mike here, or visit Mike’s main Historic Theatre Photography website here. Continue below for the full roundup on Mike’s passion project: Atmospheric Theatres!

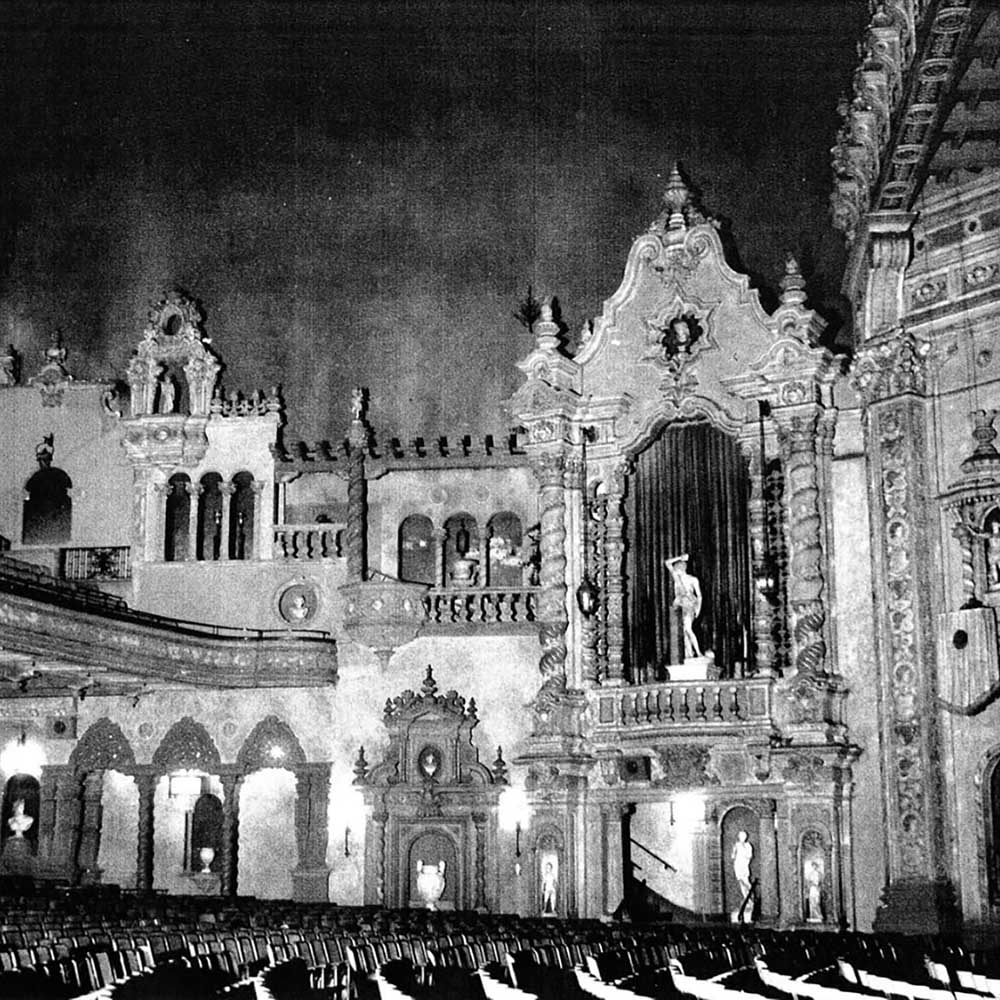

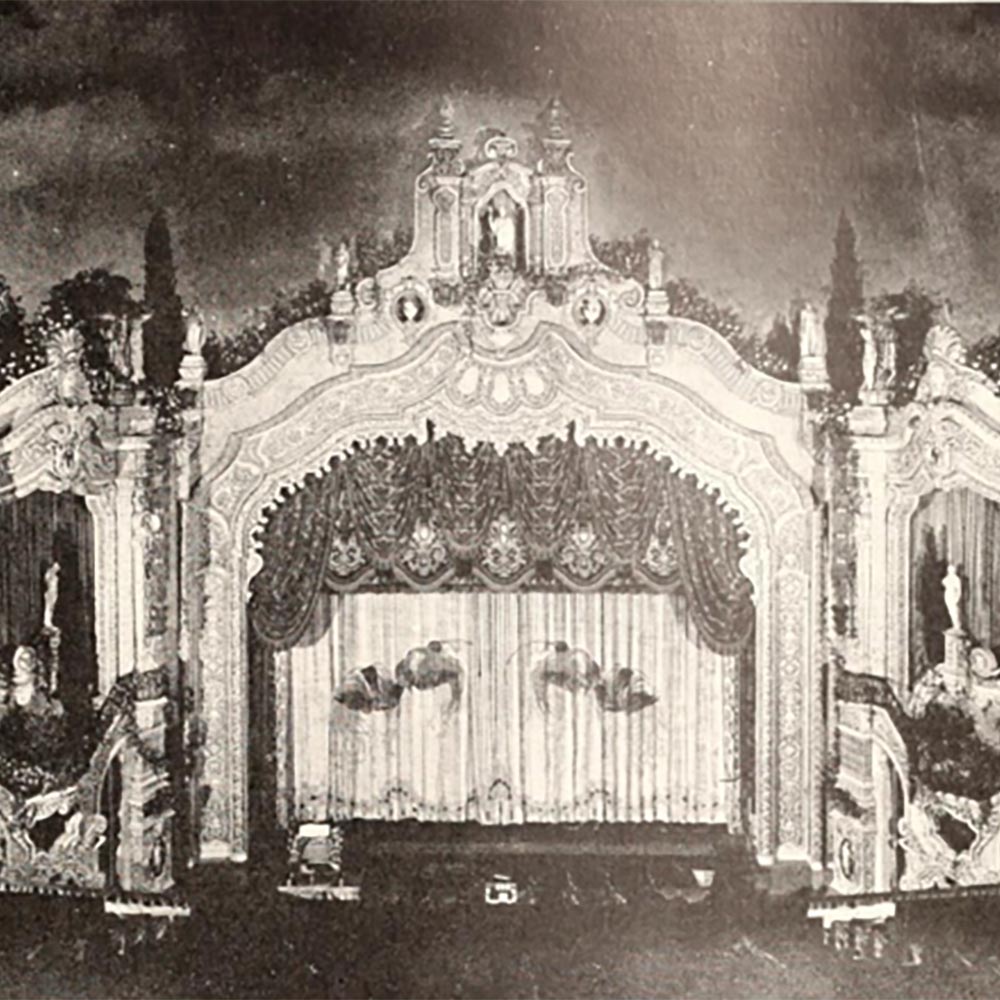

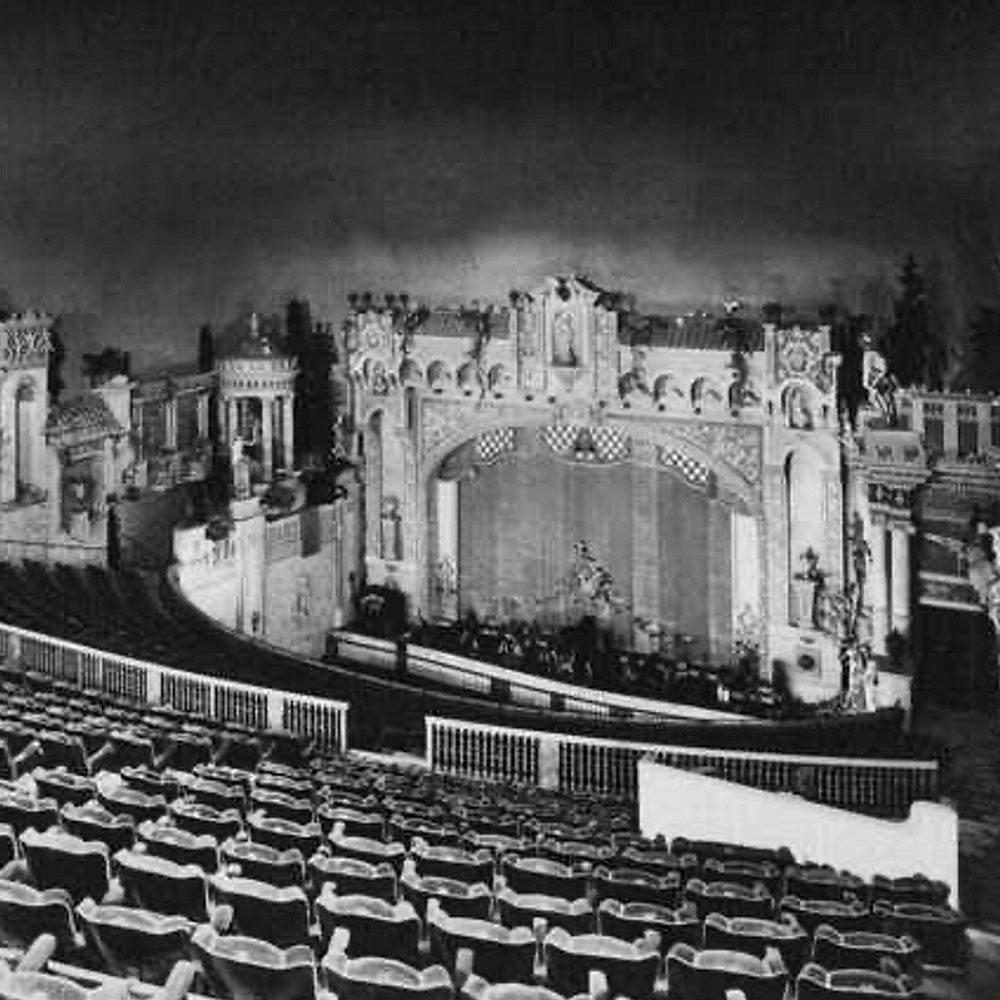

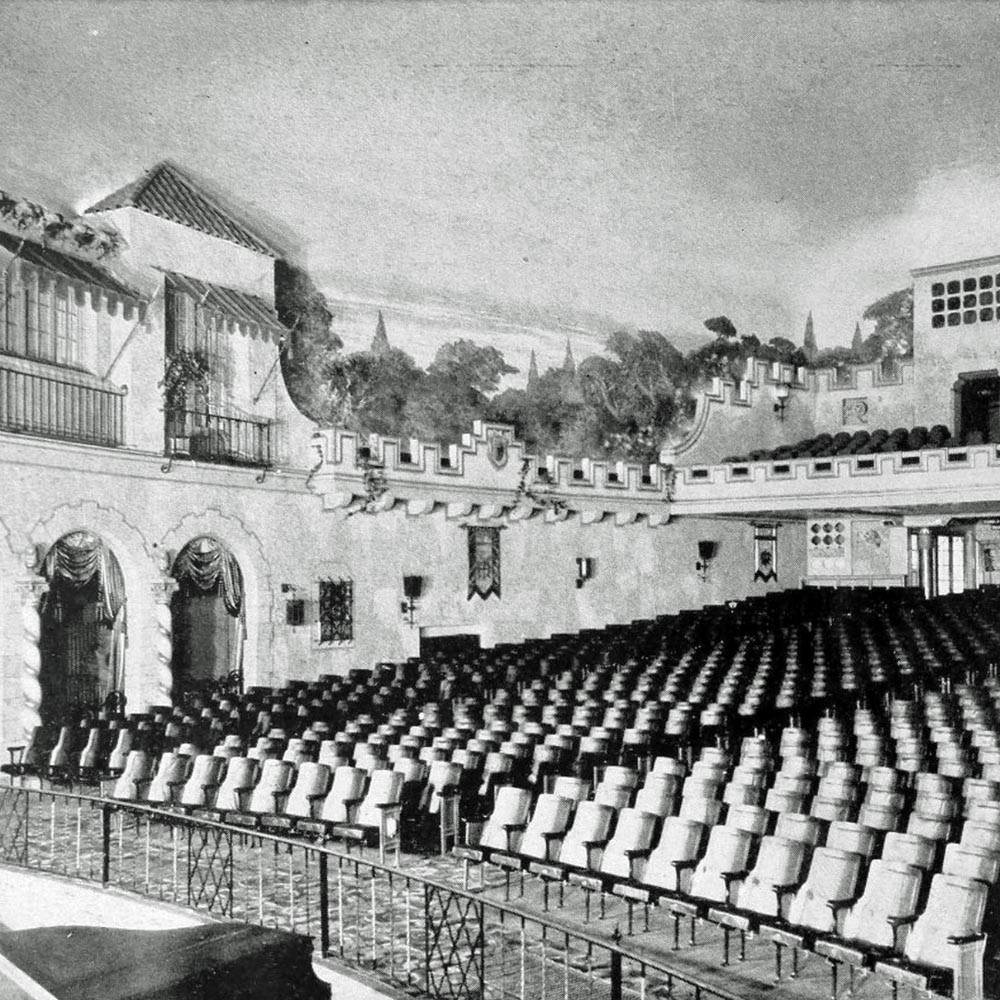

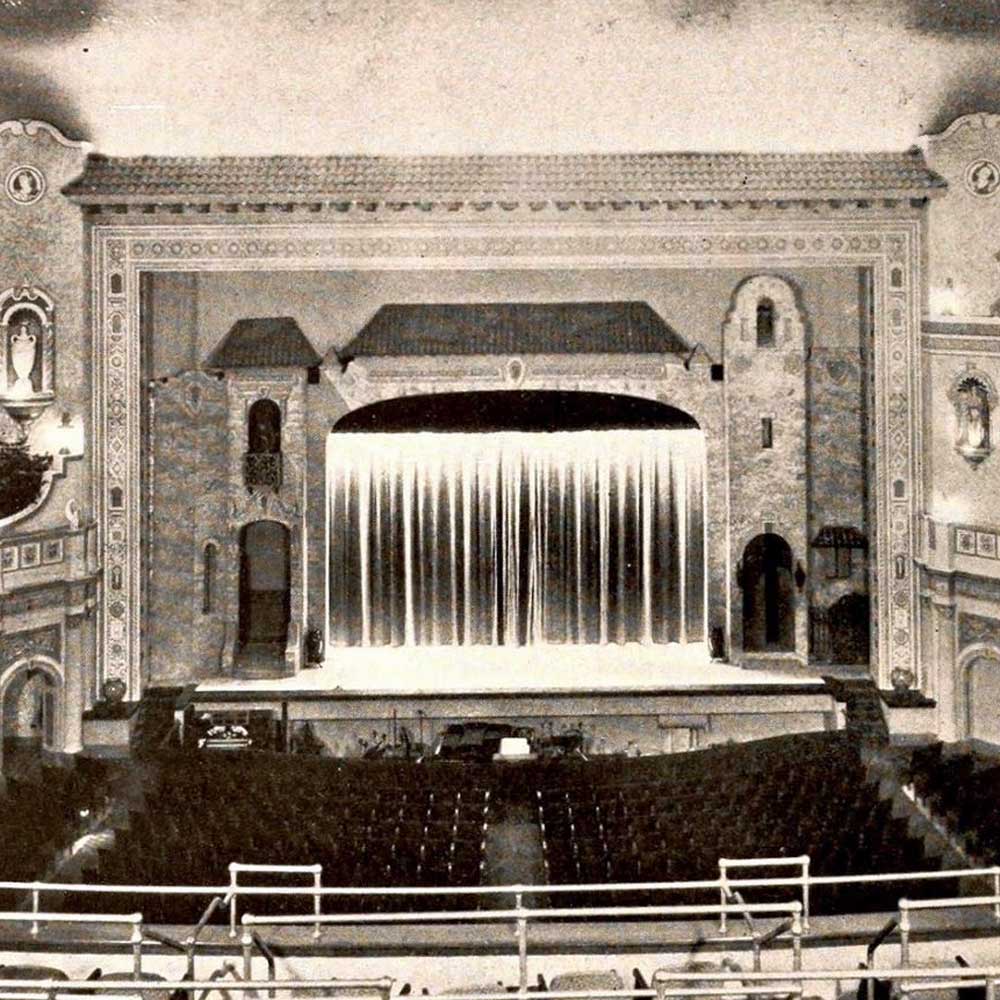

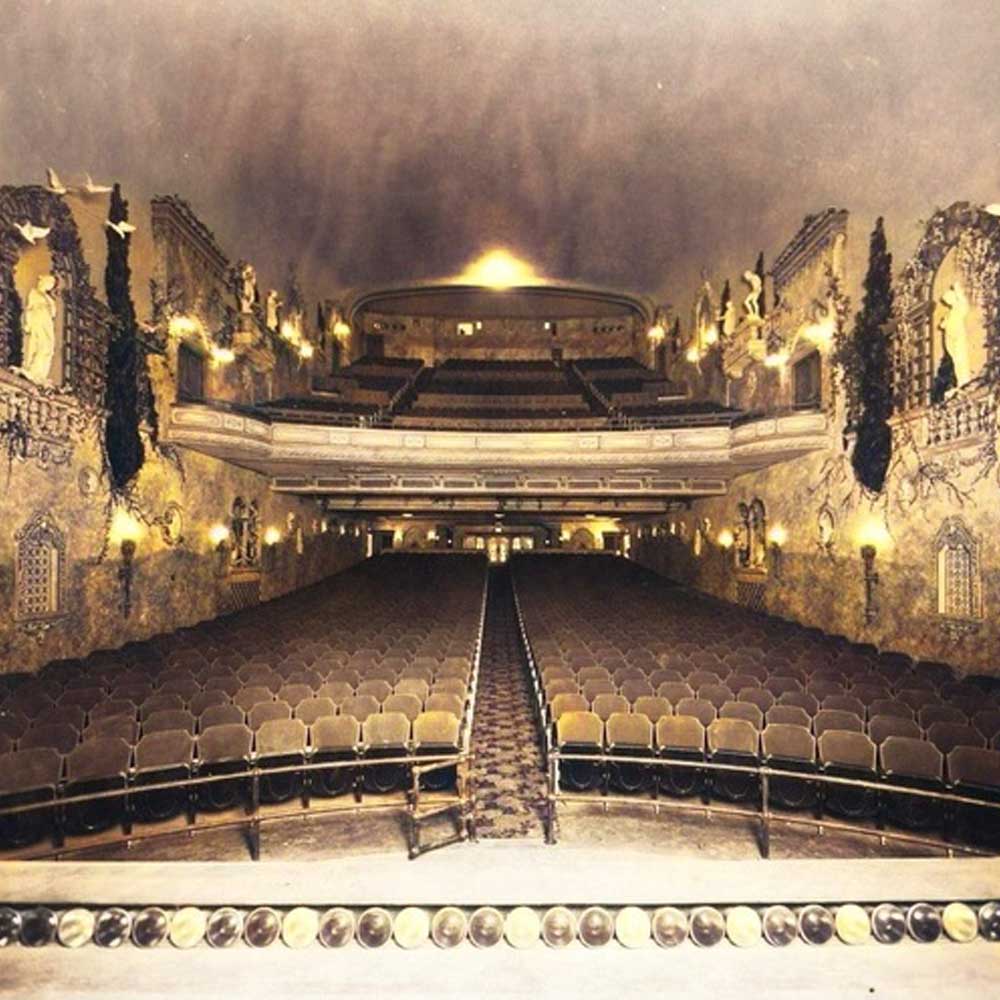

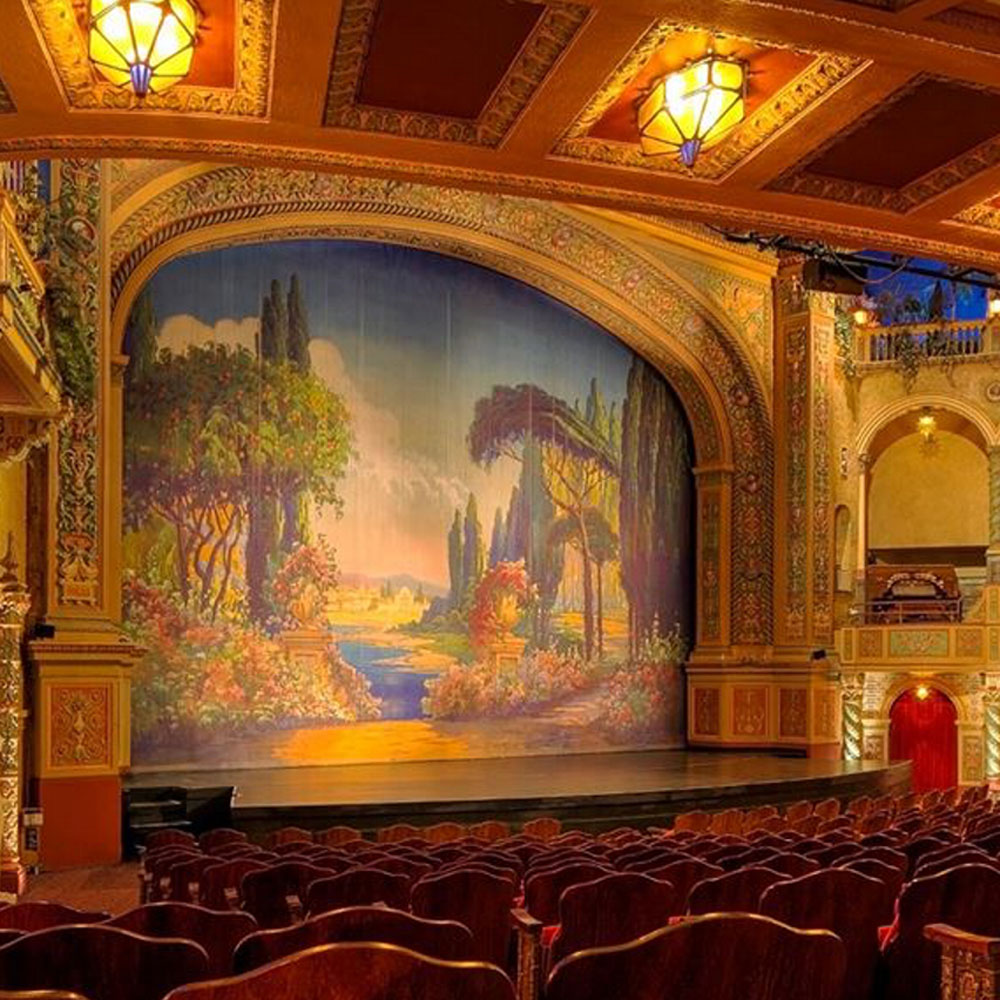

The Atmospheric theatre style was designed to evoke the sense of being transported to an exotic outdoor location. Far-away places were considered exotic and so in America that often meant European cities, places which most Americans would never have the chance to visit.

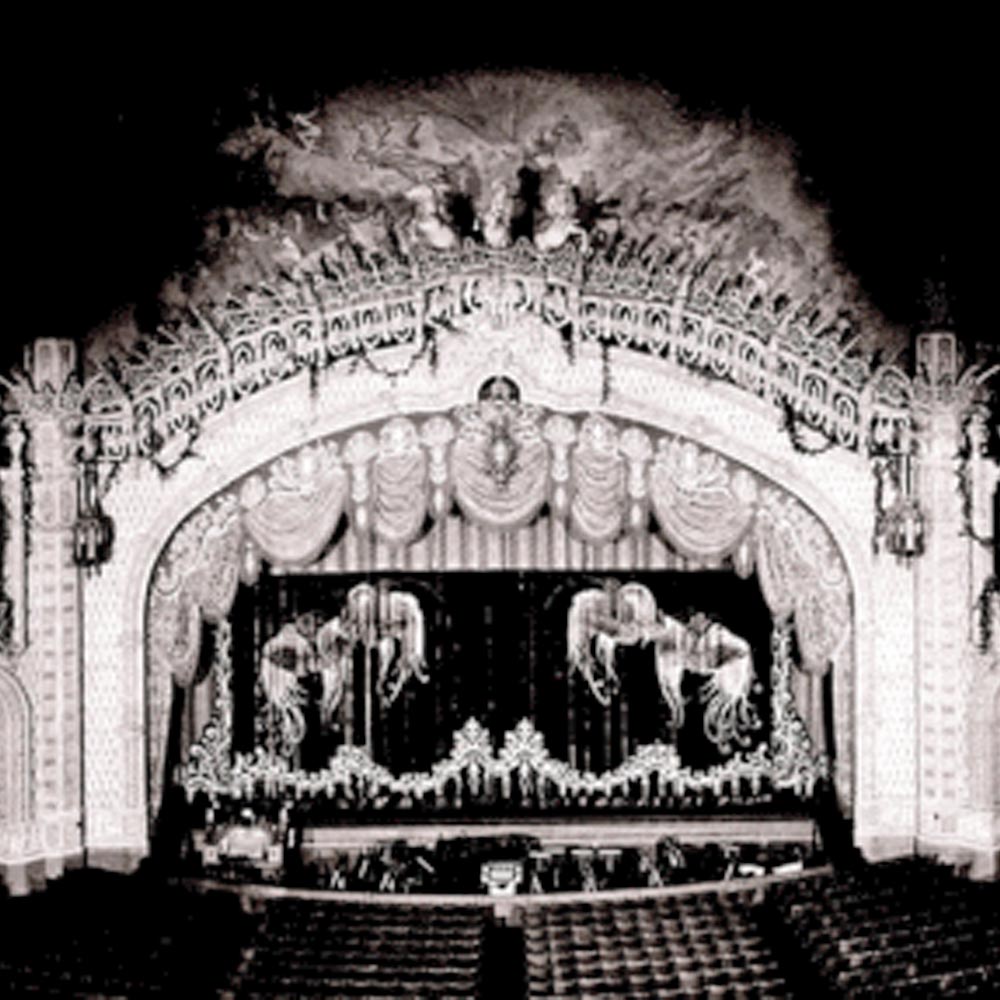

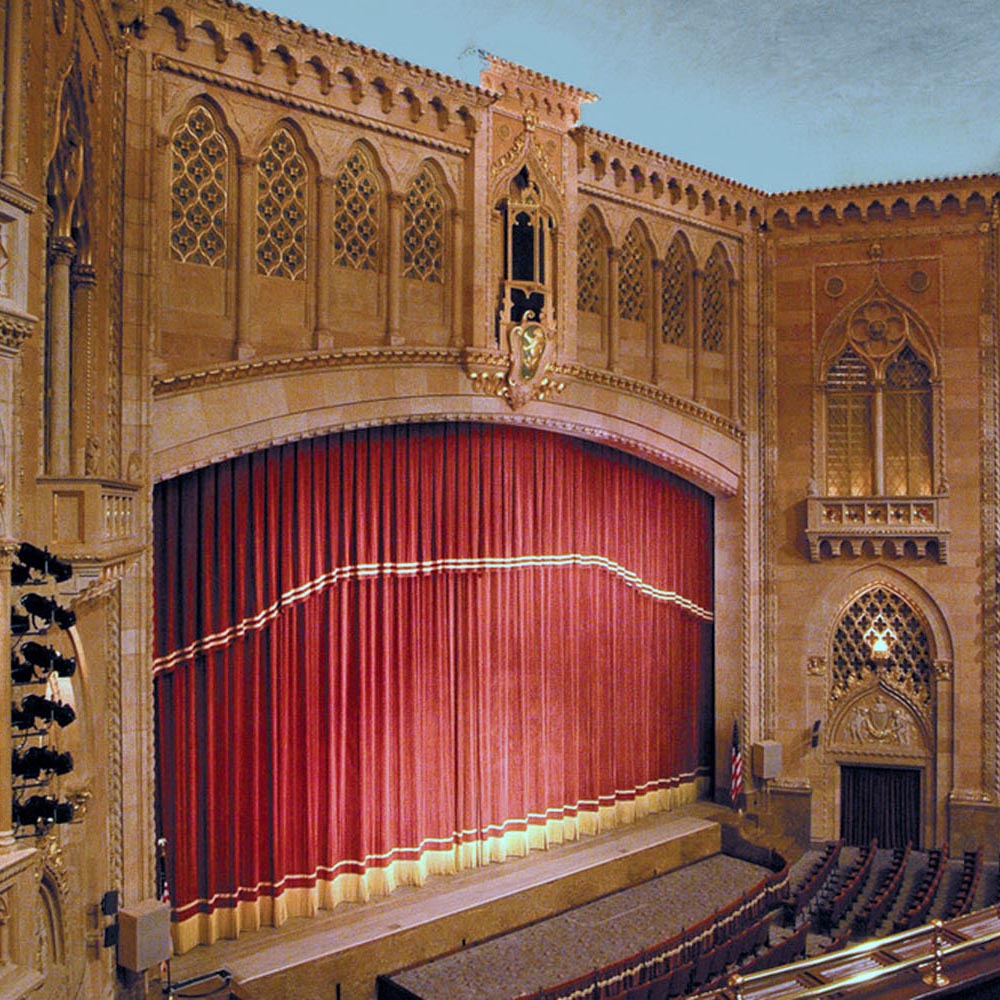

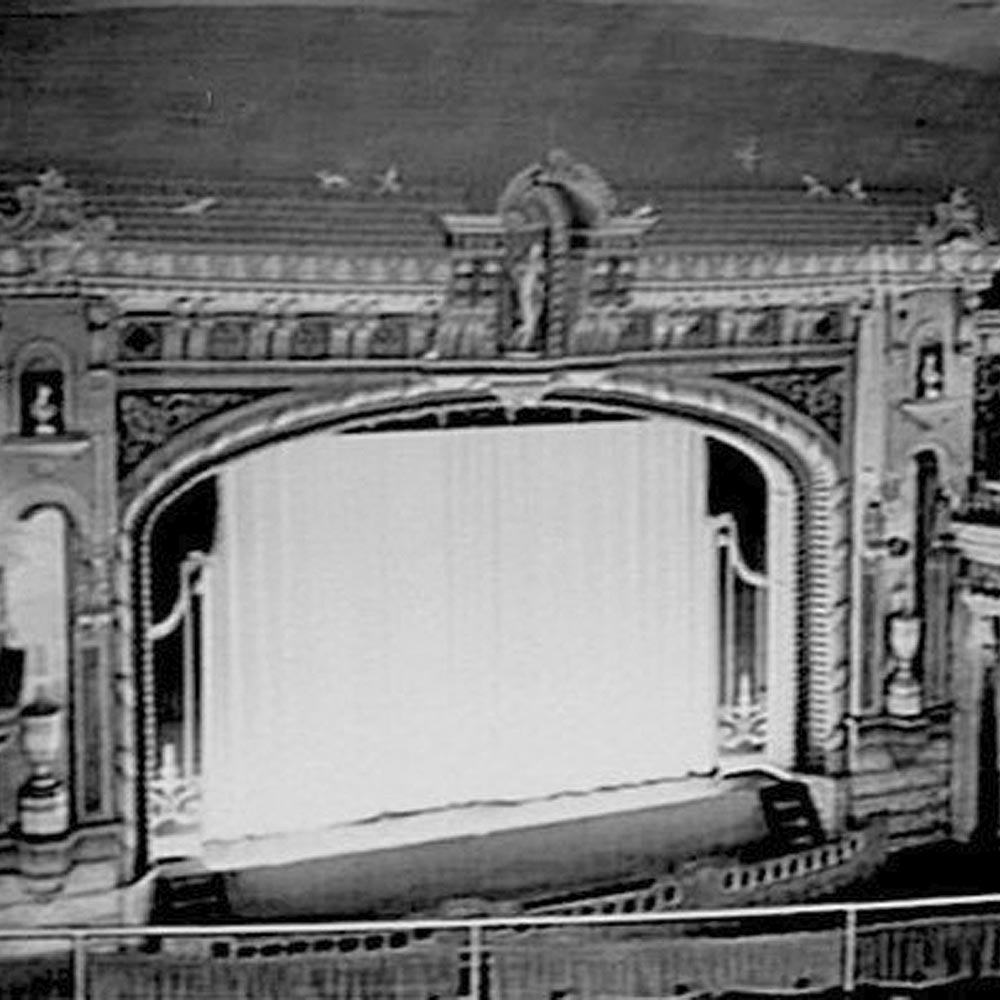

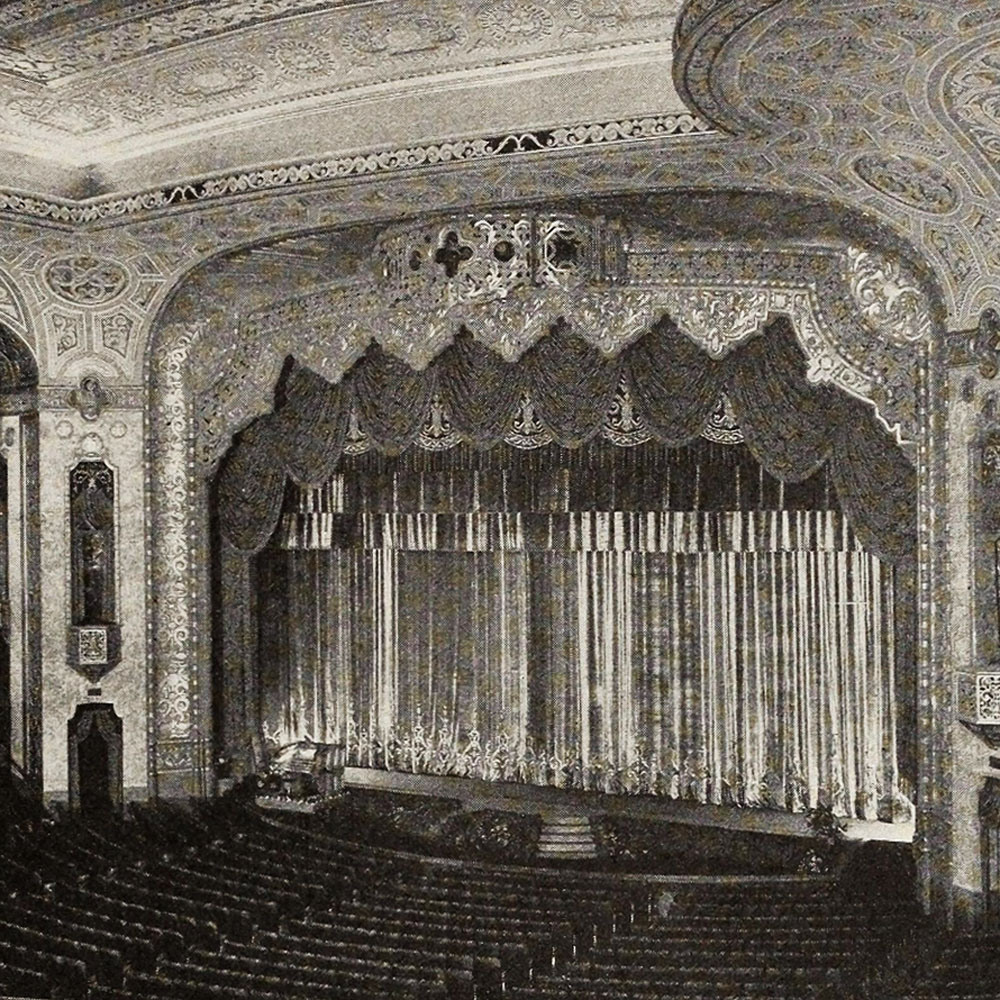

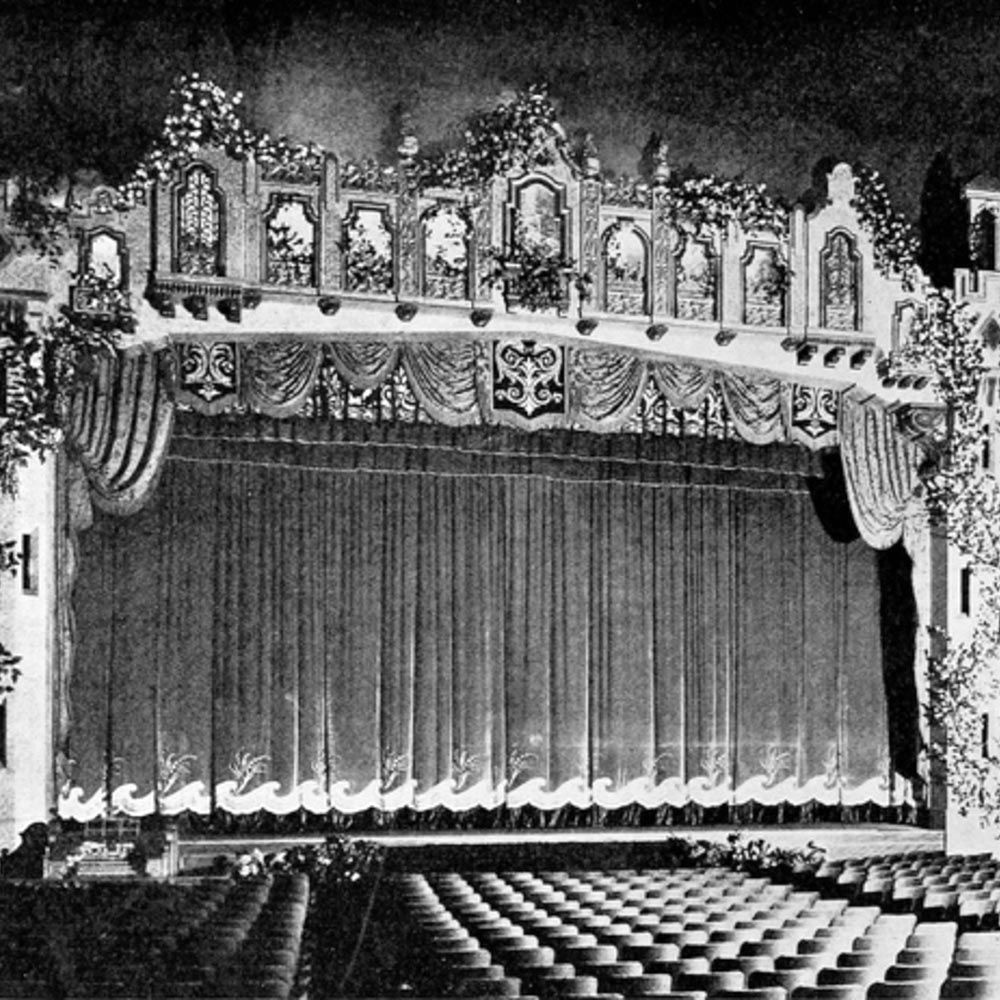

Atmospheric theatres were a phase in the evolution of theatre design which followed the grand American theatres and movie palaces of the 1910s and early 1920s, largely modeled on the design of European opera houses; but before the Great Depression took hold leading to increased levels of austerity coupled with the desire to shun opulence, and instead embrace a streamlined modernistic approach with an eye to the future.

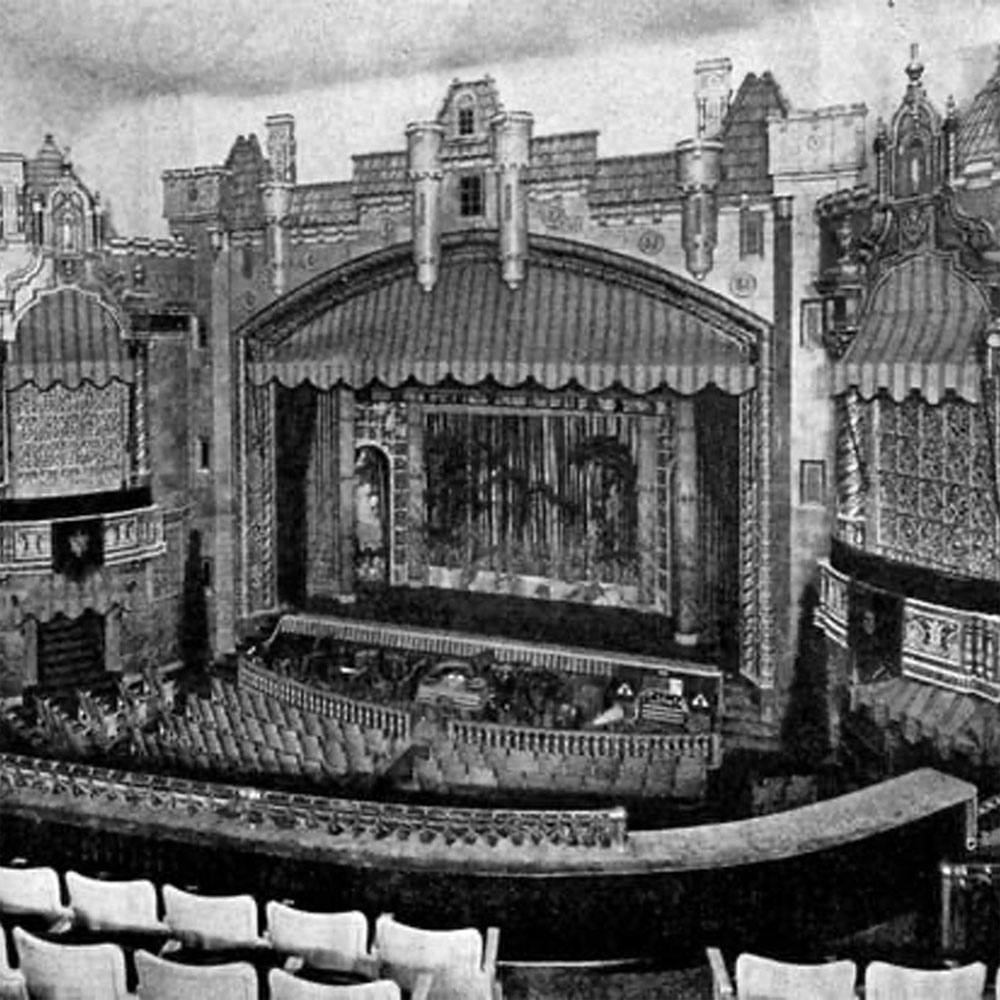

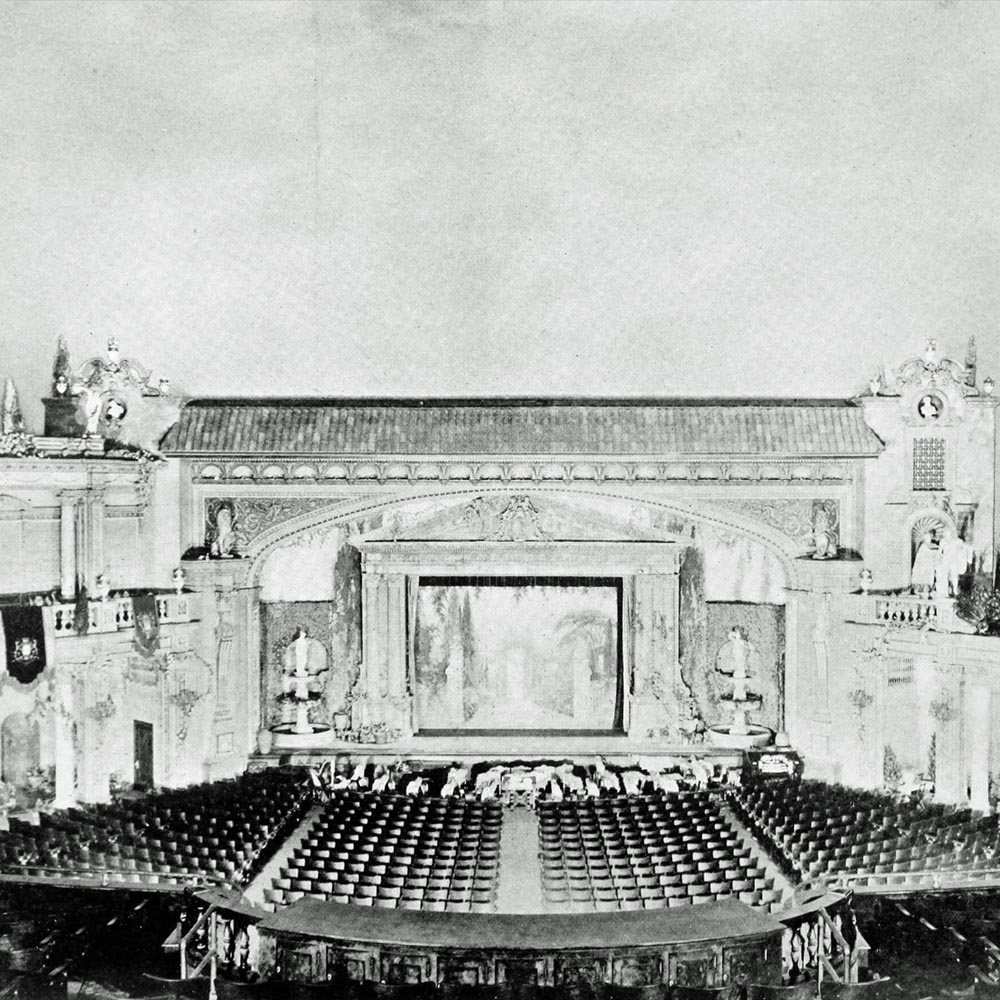

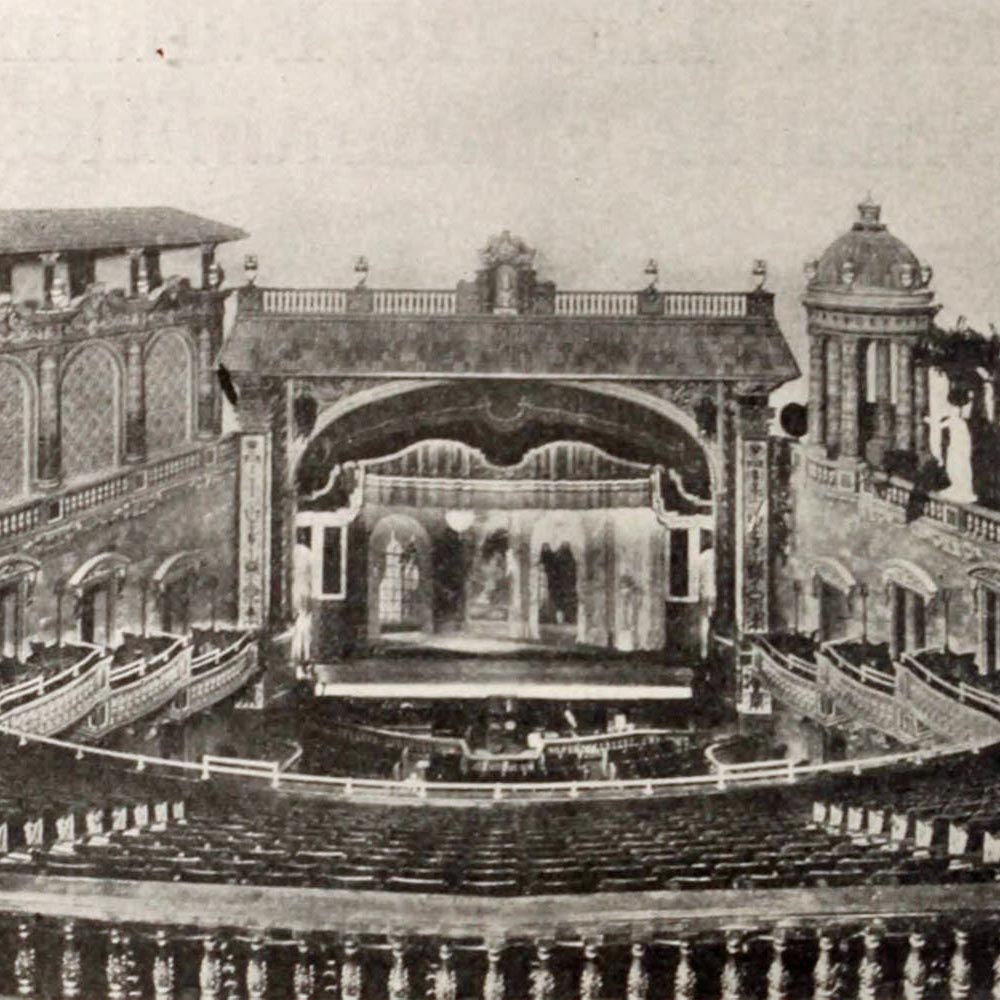

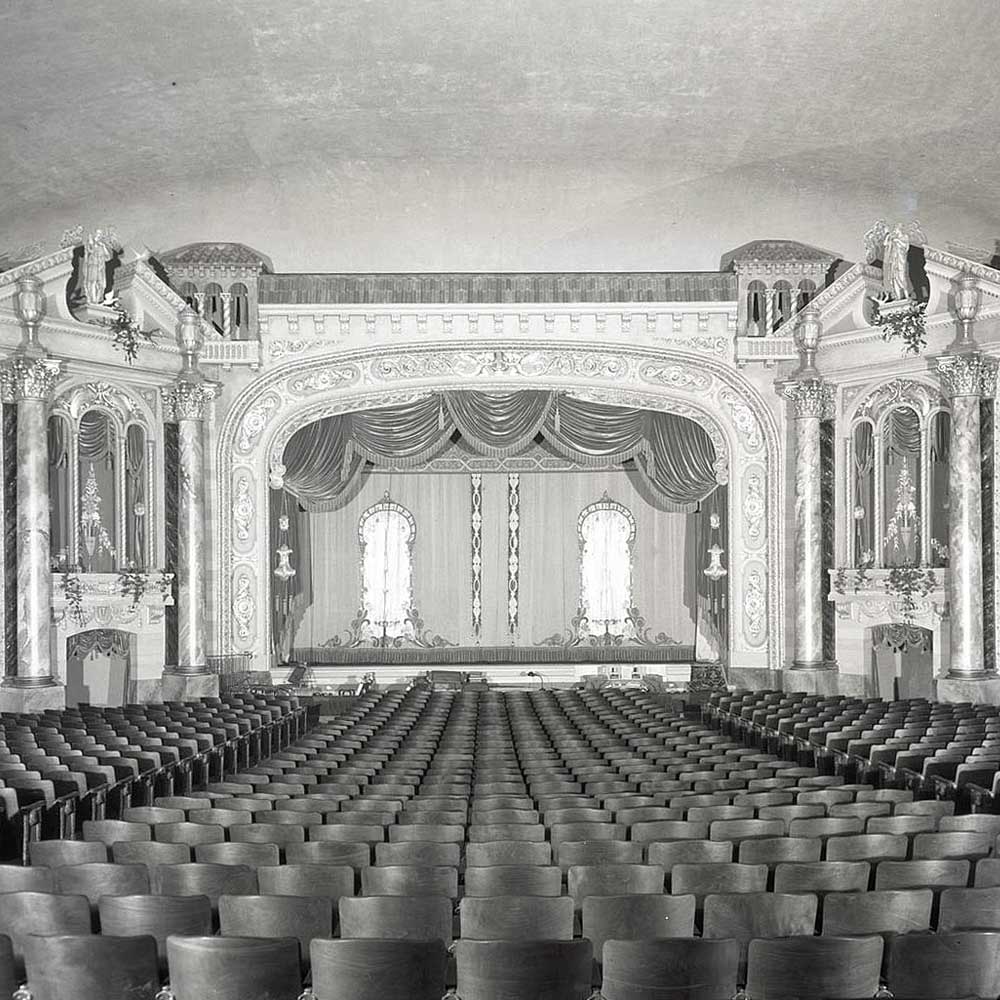

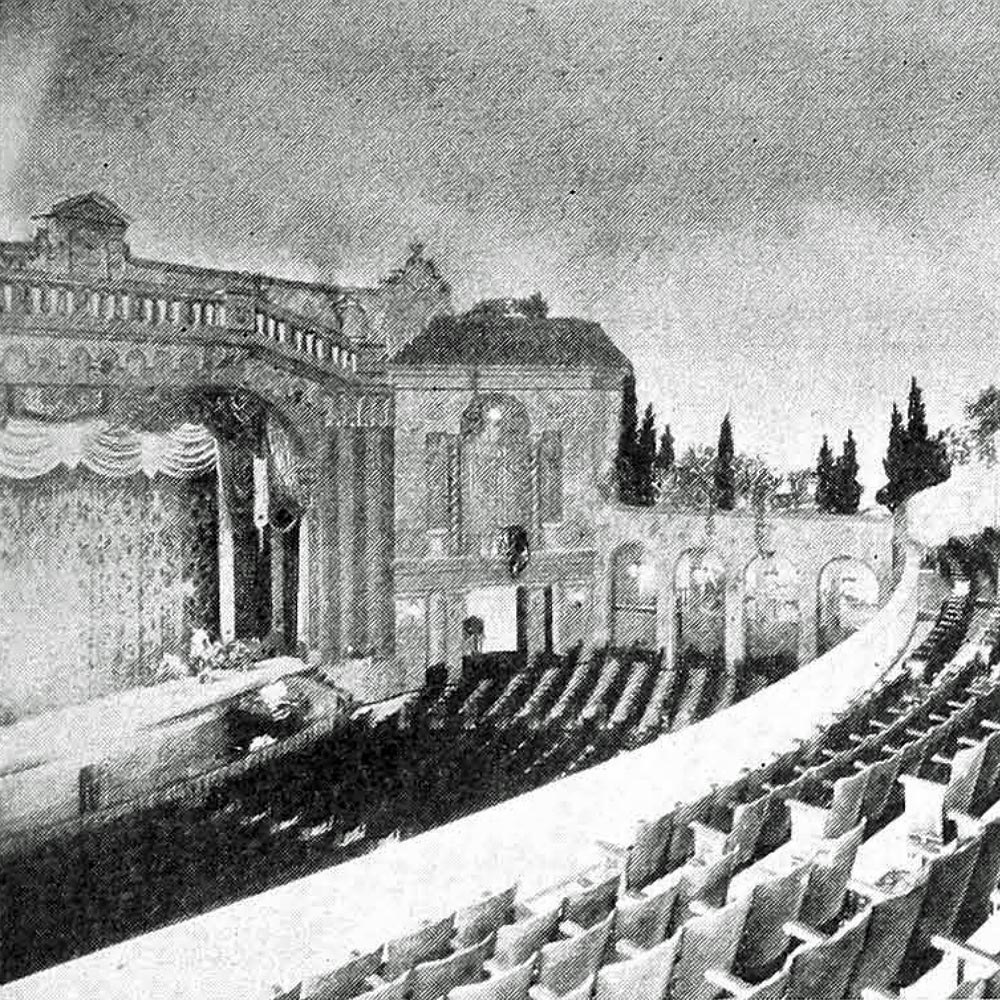

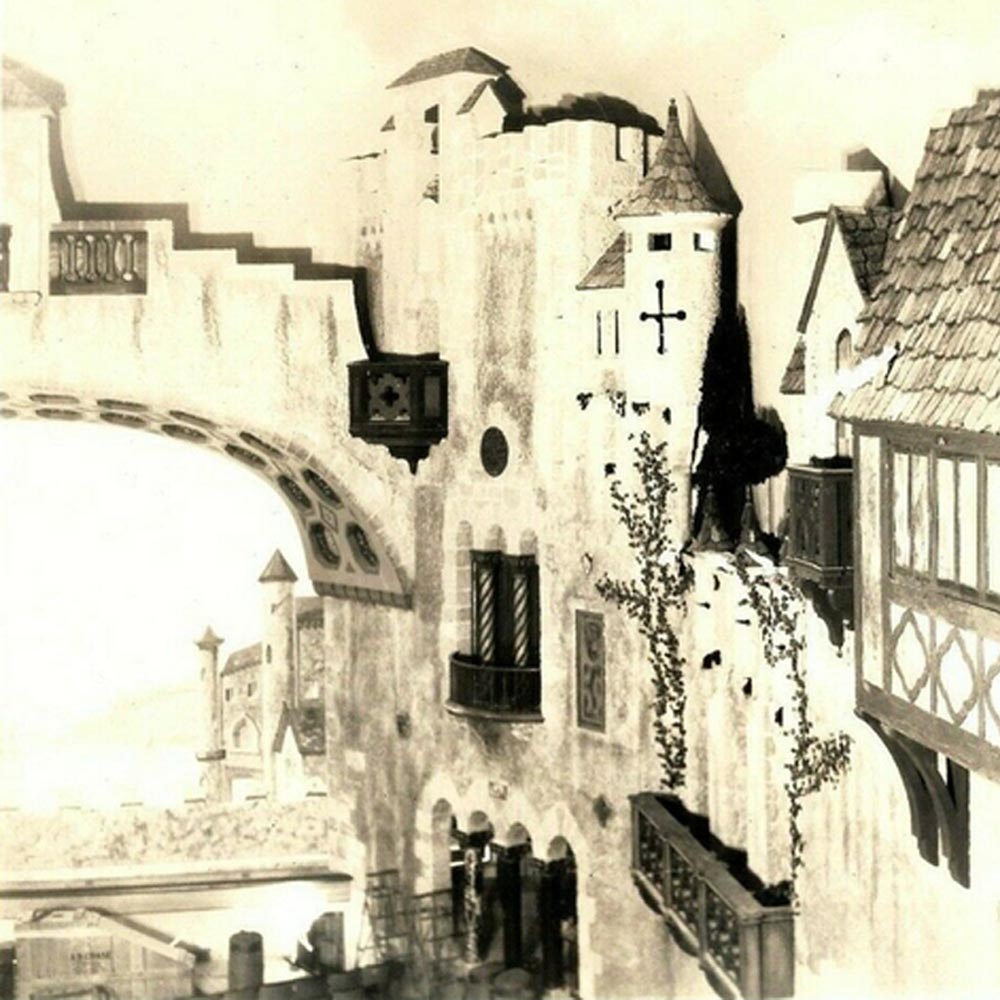

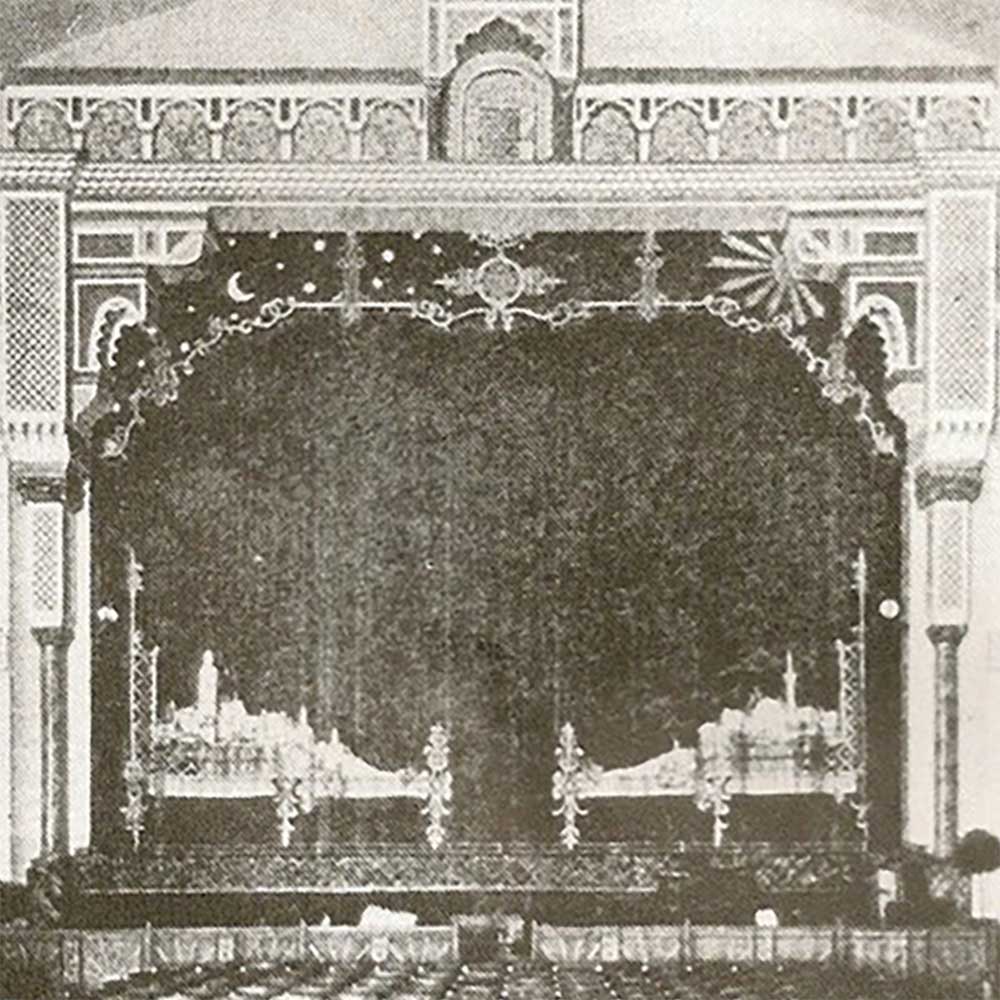

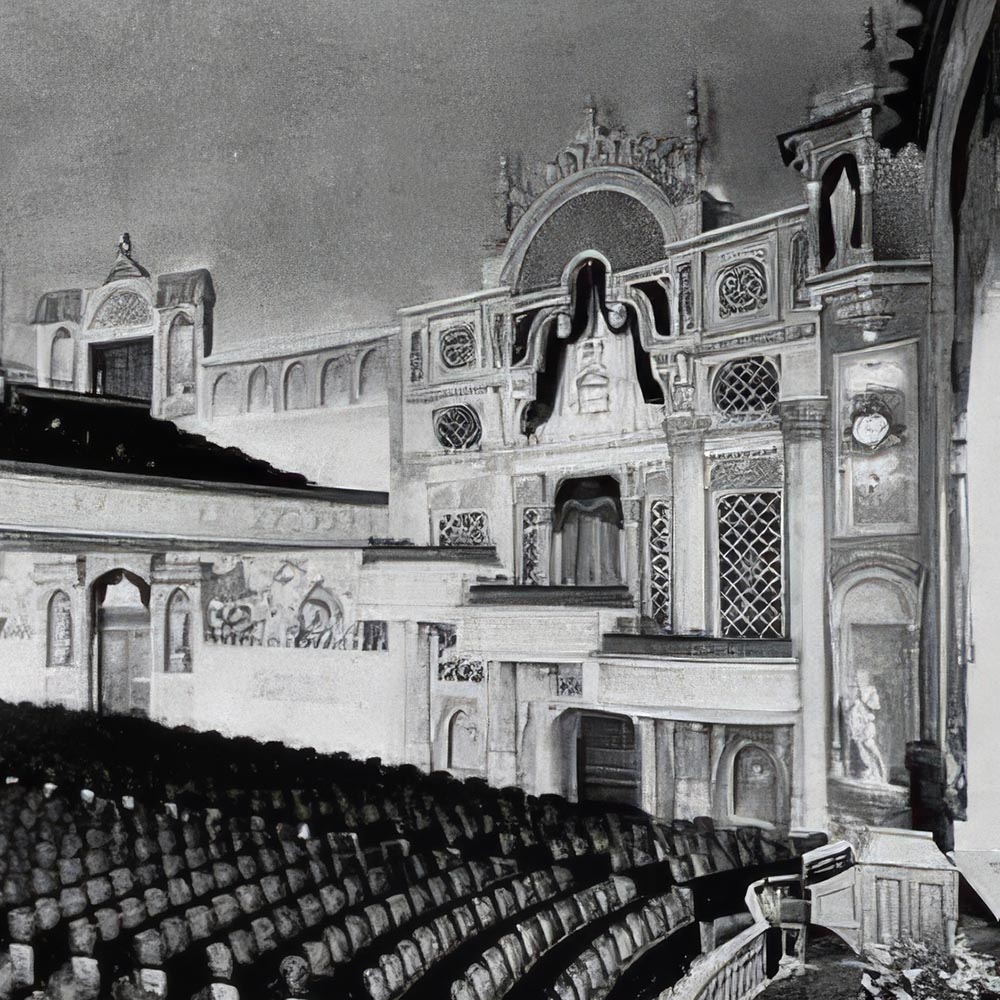

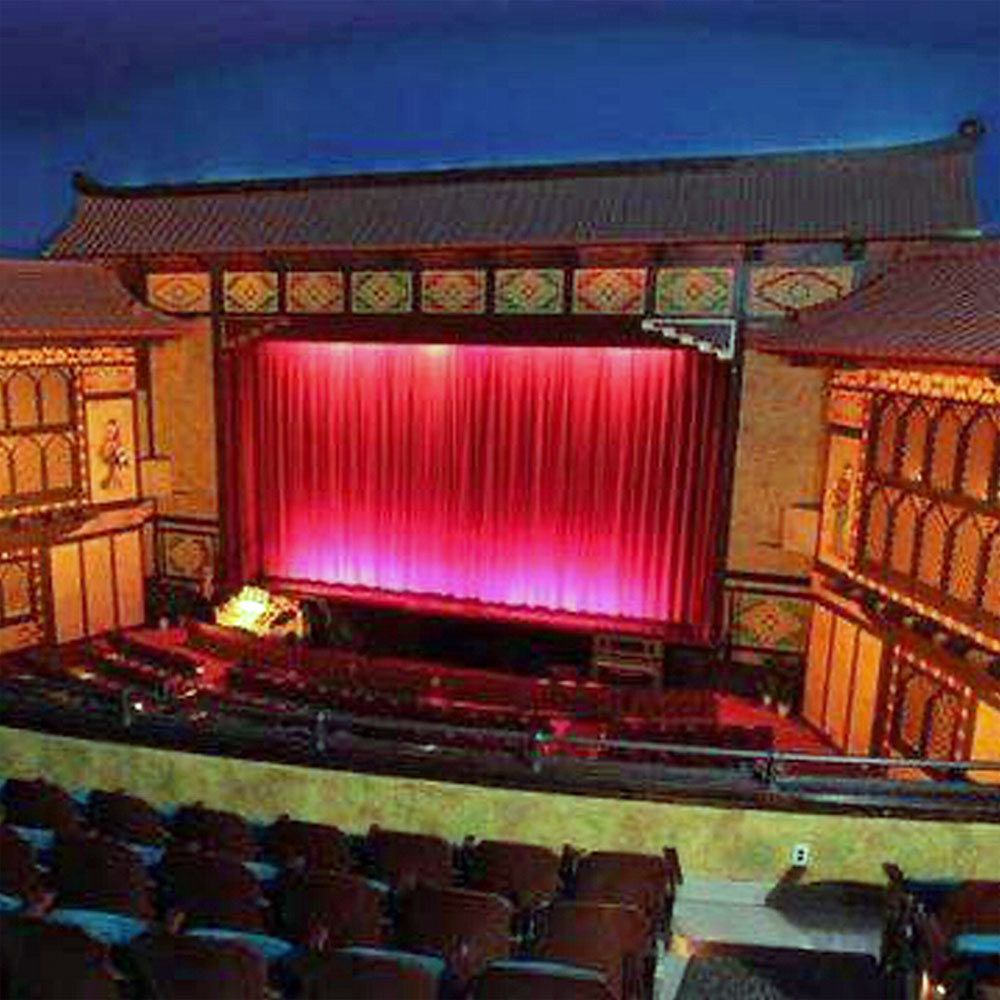

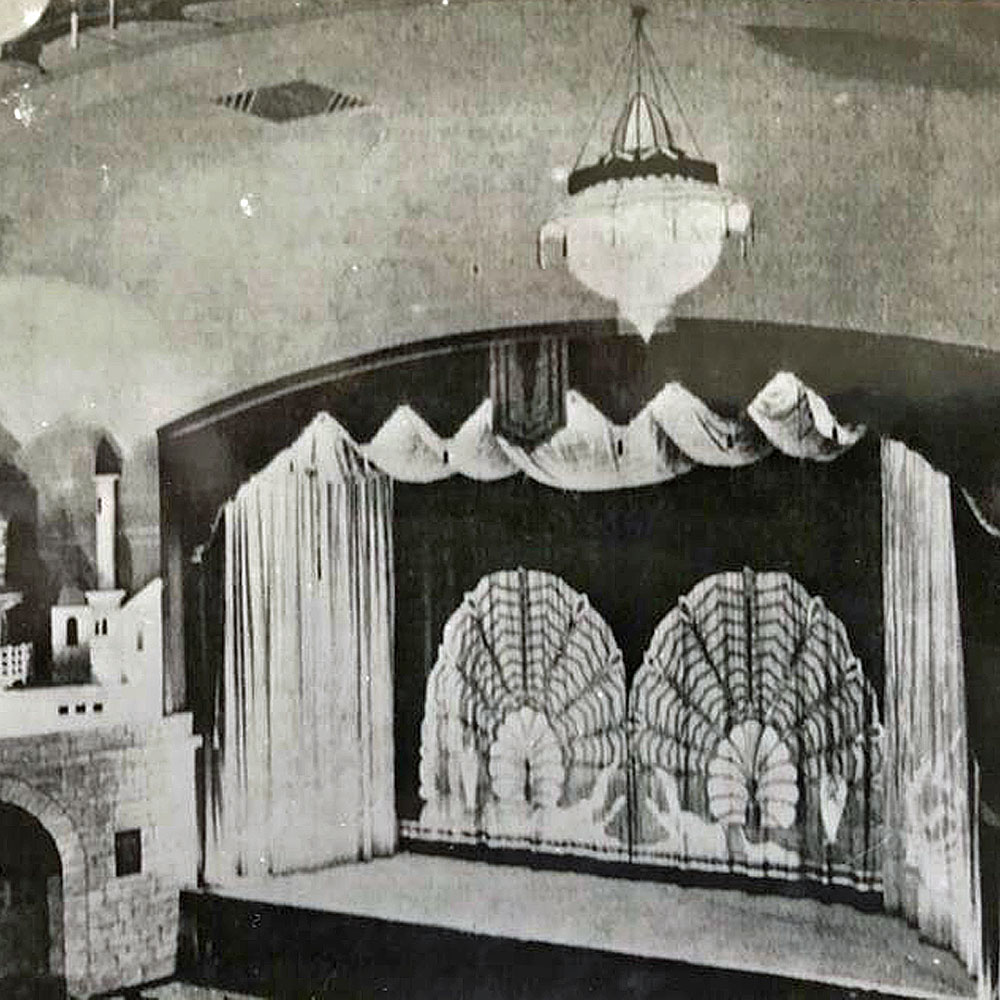

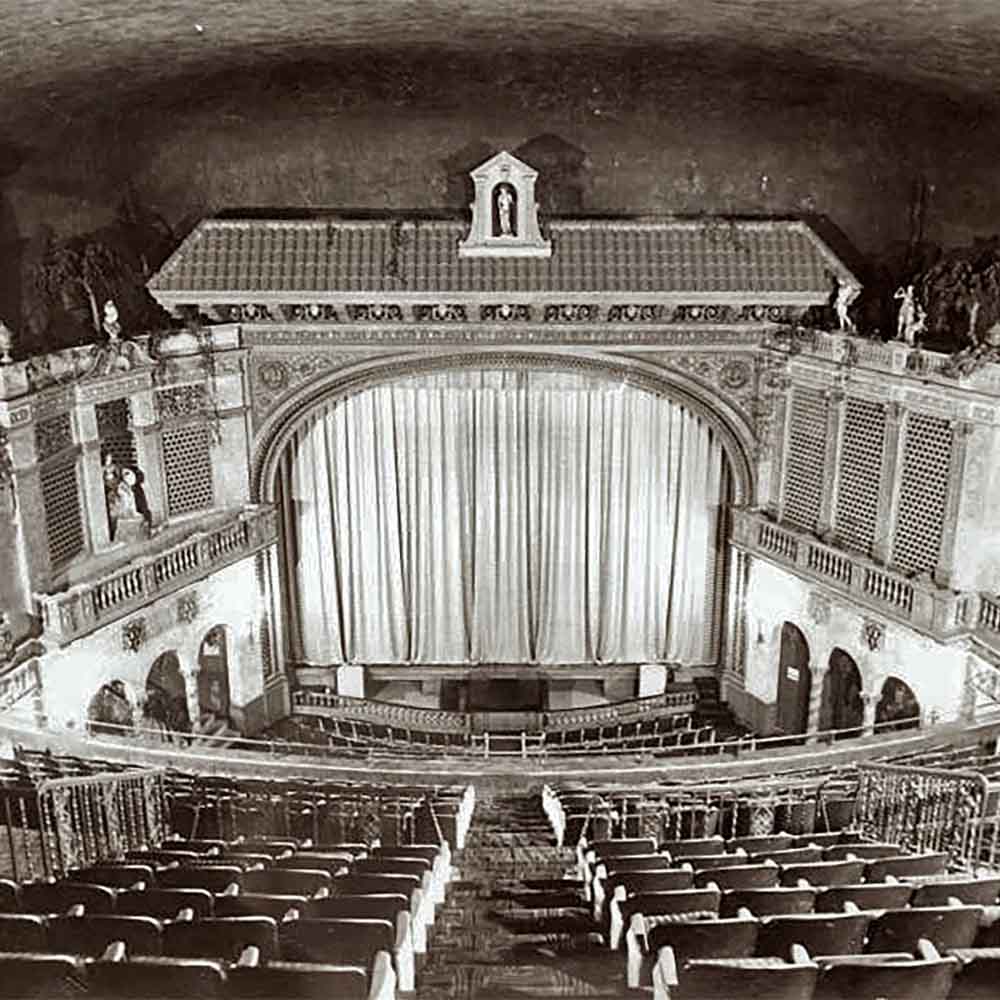

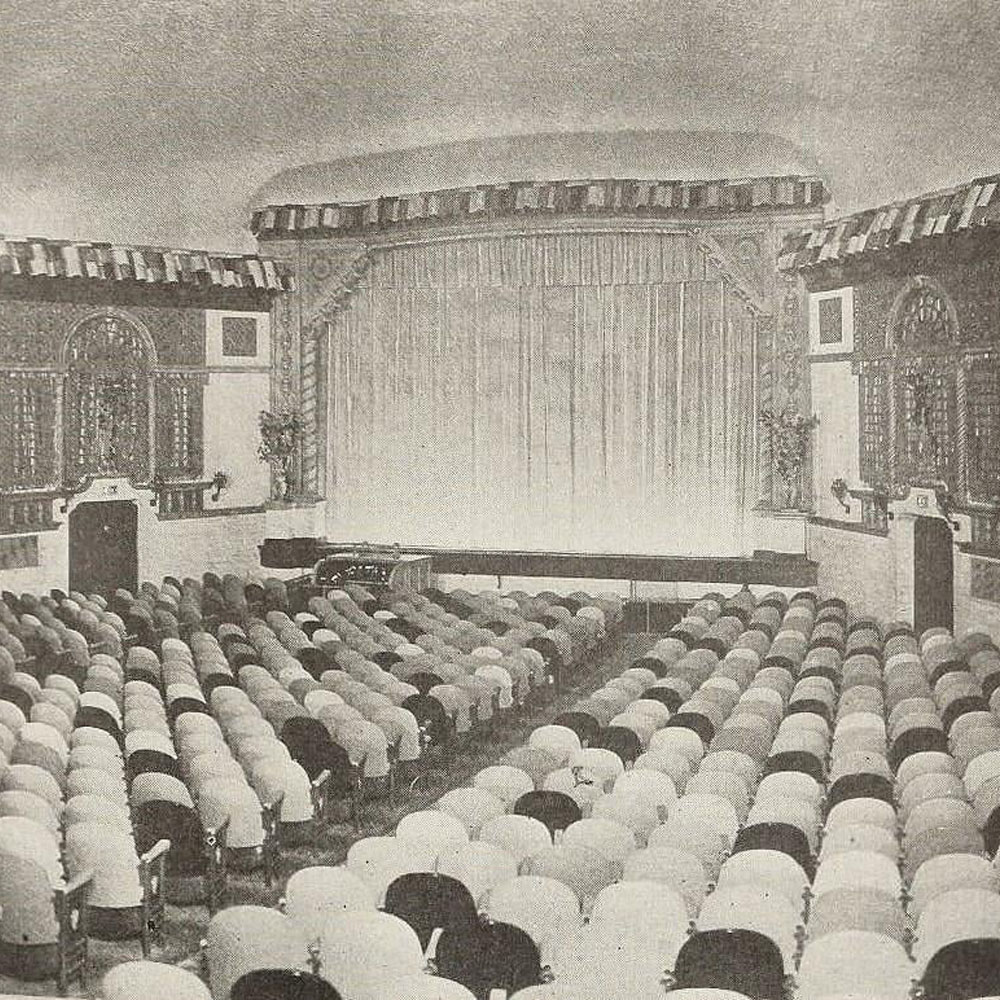

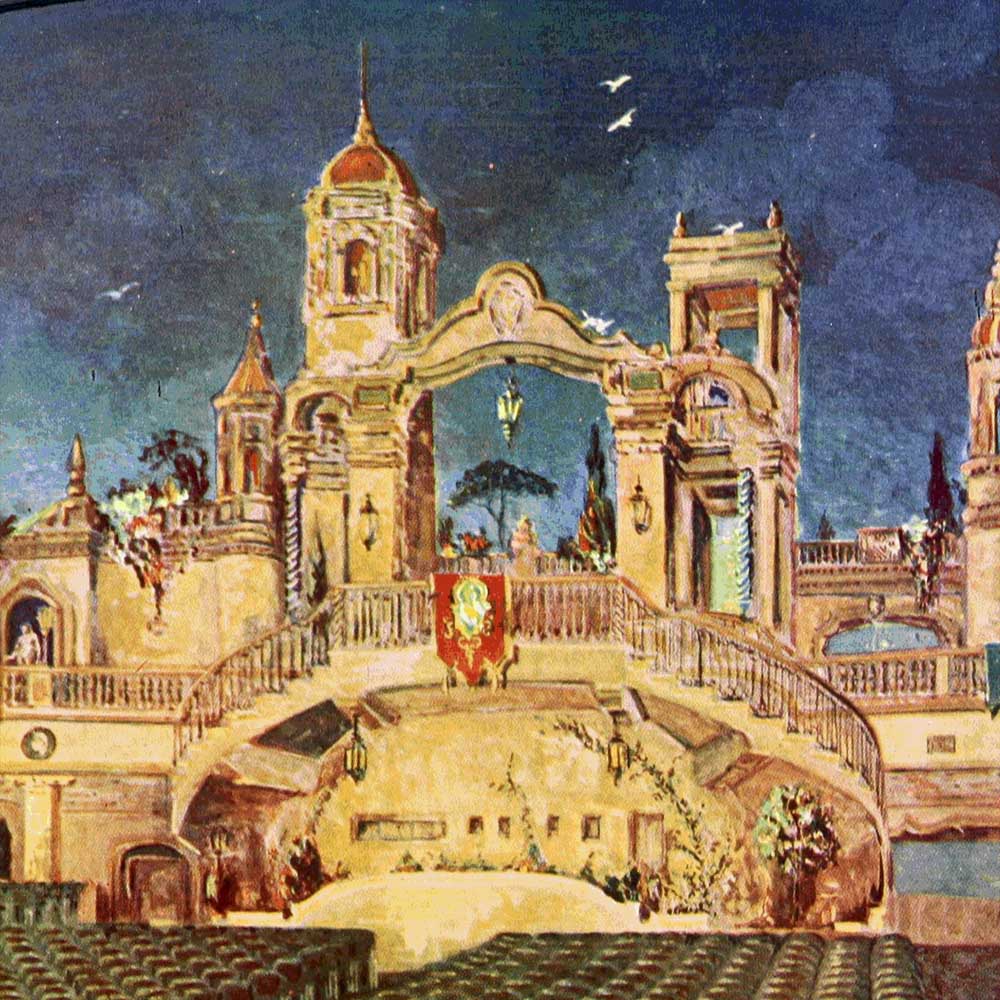

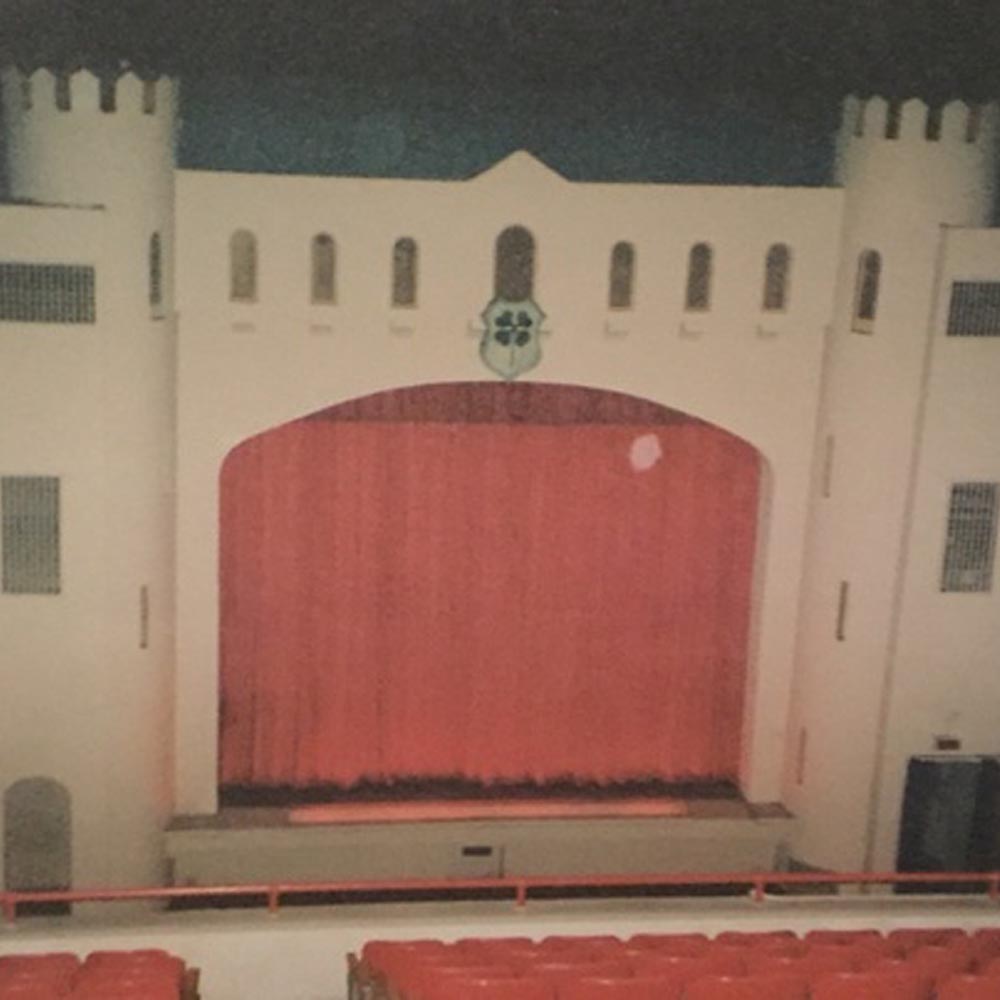

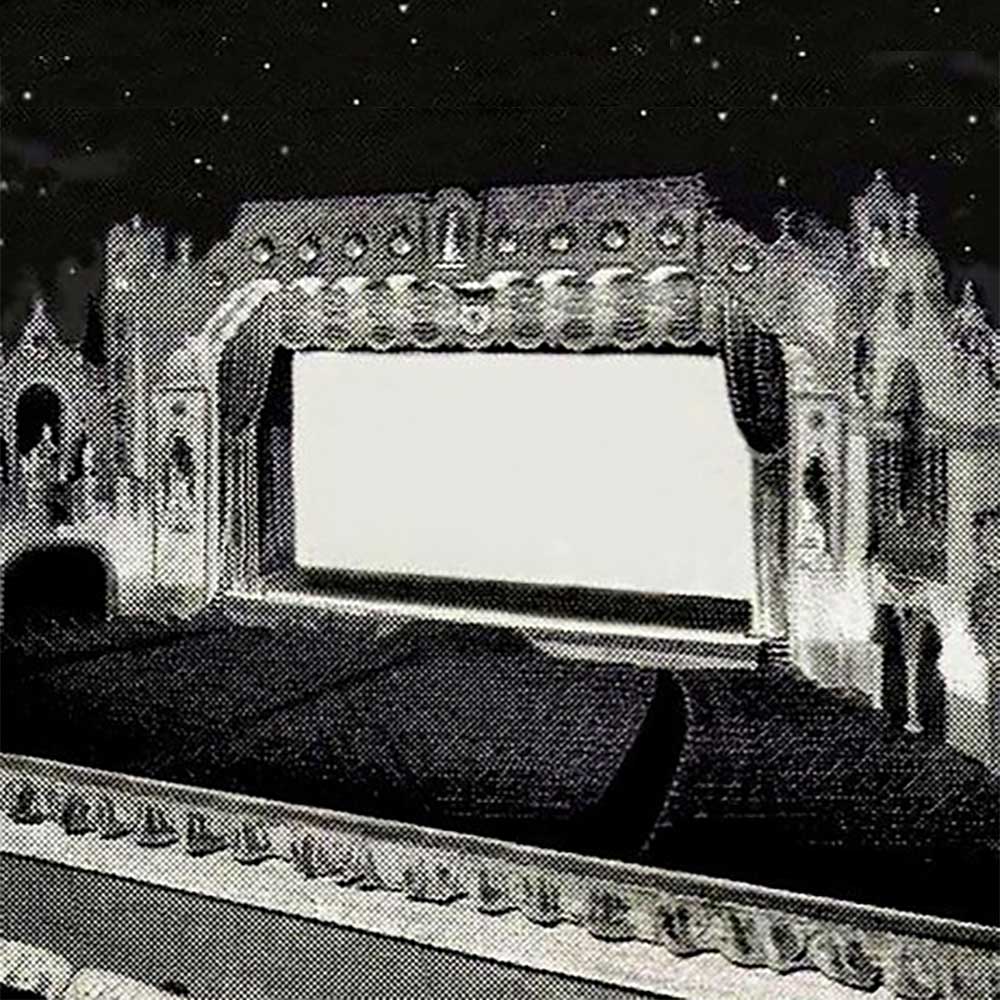

The Atmospheric theatre style eschewed the formal, box-like symmetrical designs of traditional theatre auditoria. Atmospheric theatres were typically asymmetrical and far more playful in their design. Atmospherics were most commonly Mediterranean or Spanish courtyards or garden settings, above which soared a cerulean or azure blue starlit sky, often with clouds drifting lazily past thanks to new technologies for the 1920s enabling the projection of moving cloud effects using light.

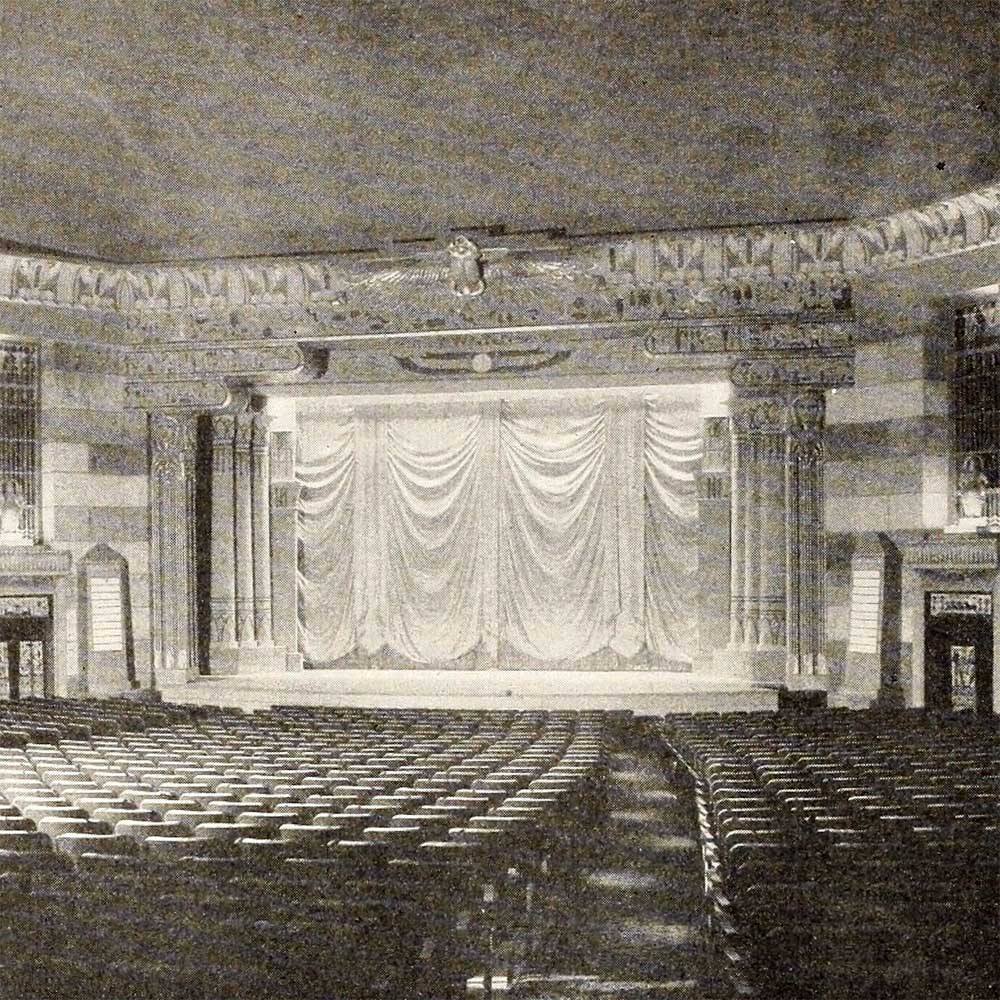

But the Atmospheric theatre style wasn’t just about creating dazzling effects for the patron: Atmospherics were also very much about the economics of running a theatre. Atmospherics cost less to build than traditional theatres – which were differentiated from Atmospheric theatres by being called “hard tops” in the United States, usually sporting an expensive central chandelier, a richly detailed plastered classical ceiling perhaps with gilded lines and accents, cherubs and caryatids adorning and supporting the balconies and boxes, and classical detailed murals.

In contrast, the Atmospheric theatre style called for a simple rounded plaster dome ceiling at a time when construction costs had escalated after the First World War and wages for ornamental plasterers had reached an all-time high.

The first Atmospheric theatre was built in early 1923, although experimentation with the emergent style was taking place as early as 1921. Accordingly, these proto-Atmospheric theatres which helped define and inform the Atmospheric style as it was being developed, are included in our listings of Atmospheric theatres.

The Atmospheric theatre style hit its stride in the mid-1920s and then peaked in 1928 and 1929. The style gradually tailed-off in the early 1930s as the Great Depression took hold and audiences clamored for more austere and less opulent surroundings.

The few Atmospheric theatres built after the mid-1930s were a design choice generally paying homage to the opulent 1920s style, and deliberately eschewing the early 1930s austere and streamlined approach to movie theatre design.

The pioneer of the Atmospheric theatre style was prolific theatre architect John Eberson. At the opening of the Tampa Theatre in Florida in October 1926, Eberson stated:

“My idea for the Atmospheric theater was born in Florida. I saw the value of putting nature to work and so have borrowed the color and design that are found in the flowers and the trees. The inhabitants of Spain and southern Italy live under the sun and enjoy the happiness nature affords them. So I decided their architecture probably would provide the firm foundation for a theater.”

Eberson was probably also influenced by other experiences, including visiting the St. Louis Word’s Fair in 1904 which would have demonstrated the solid and permanent appearance of plasterwork while being used as an impermanent construction material, and Chicago’s Cort Theater  (opened 1909, demolished 1934) designed by John E.O. Pridmore which featured a Roman pergola with vine-clad beams and a blue sky ceiling above; an outdoor overhead setting for what was otherwise a traditional traditional auditorium design.

(opened 1909, demolished 1934) designed by John E.O. Pridmore which featured a Roman pergola with vine-clad beams and a blue sky ceiling above; an outdoor overhead setting for what was otherwise a traditional traditional auditorium design.

Eberson devised a business model which saw his own centralized studio – the Michel Angelo Studios, Inc. of Chicago, and later New York – mass produce works for the theatres he designed. The studio, overseen by Eberson’s wife Beatrice (Beatty) Lamb, was staffed with dedicated master plasterers and created statuary, moldings, and architectural components which Eberson would then re-use across multiple theatre designs, rearranging the separate elements into different settings, thereby reducing the cost of building a theatre simply through the economics of reuse.

The model also meant that Eberson could control the quality of product from start to finish by using his own master plasterers and installation crews. Construction on-site was simplified and therefore costs reduced because ready-made statuary and architectural elements arrived in crated packages and just needed assembled on-site, and then painted, by Eberson’s traveling theatre installation teams.

Eberson declared the Majestic Theatre in Houston, Texas, as the first Atmospheric theatre. The evolution of his theatre designs leading up to this point form a series of what we now refer to as Proto-Atmospheric theatres.

General research has established that Eberson designed three Proto-Atmospheric theatres prior to his self-proclamation of the new Atmospheric theatre style in January 1923. However, through extensive research we discovered in May 2025 the revelation that Eberson designed “an outdoor theatre inside” five years before any of his established Proto-Atmospherics. This pre-Proto-Atmospheric was the Palace Theatre in Flint, Michigan, which opened in mid-1917 with an auditorium described as “a Roman Garden, bounded by ancient stone walls and a pergola of beams above, all under a Roman sky”. It was noted in newspaper reports that the “sky” featured twinkling stars.

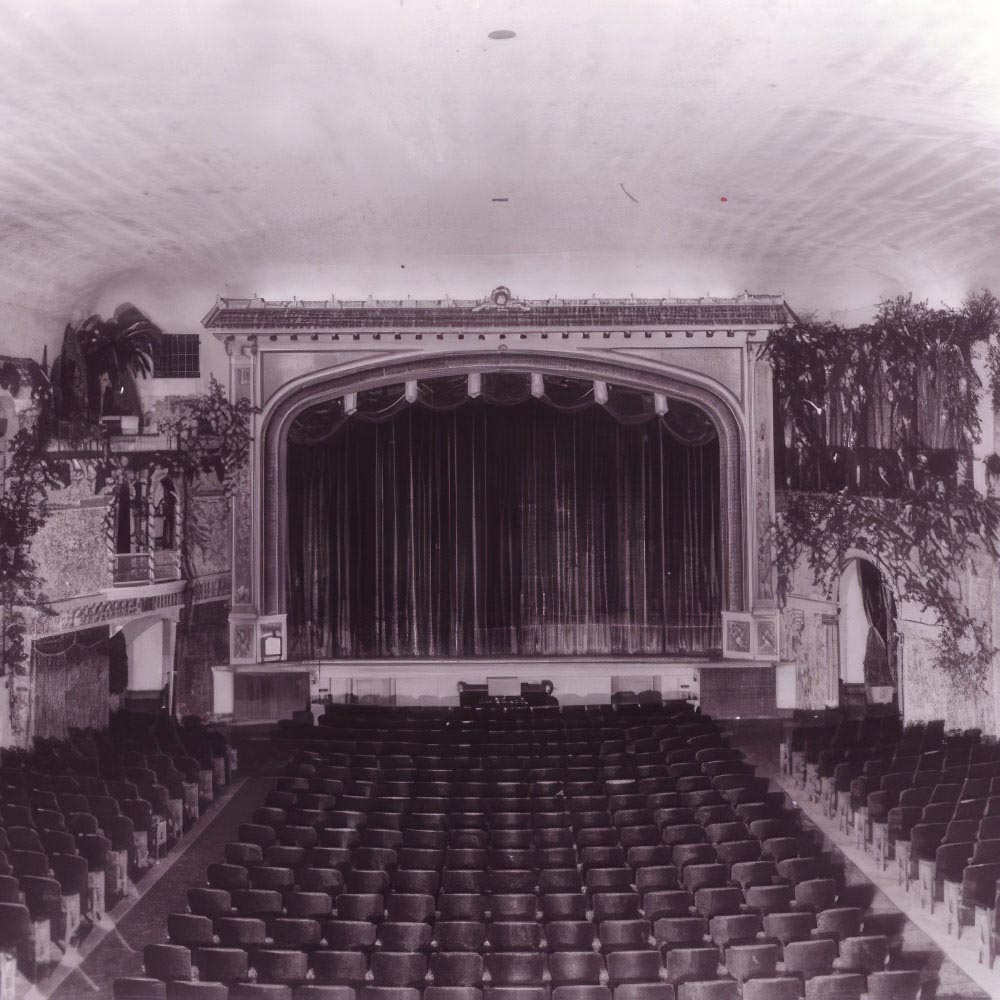

Aside from ongoing research on the Palace Theatre in Flint, Michigan, the Majestic Theatre in Dallas, Texas, was Eberson’s first Proto-Atmospheric. Opened April 1921, it sports a mix of formal Corinthian columns surrounding a triumphal proscenium arch, with symmetrical organ grilles giving way to latticework with a plain blue-lit ceiling behind...perhaps suggestive of a cerulean blue night sky?

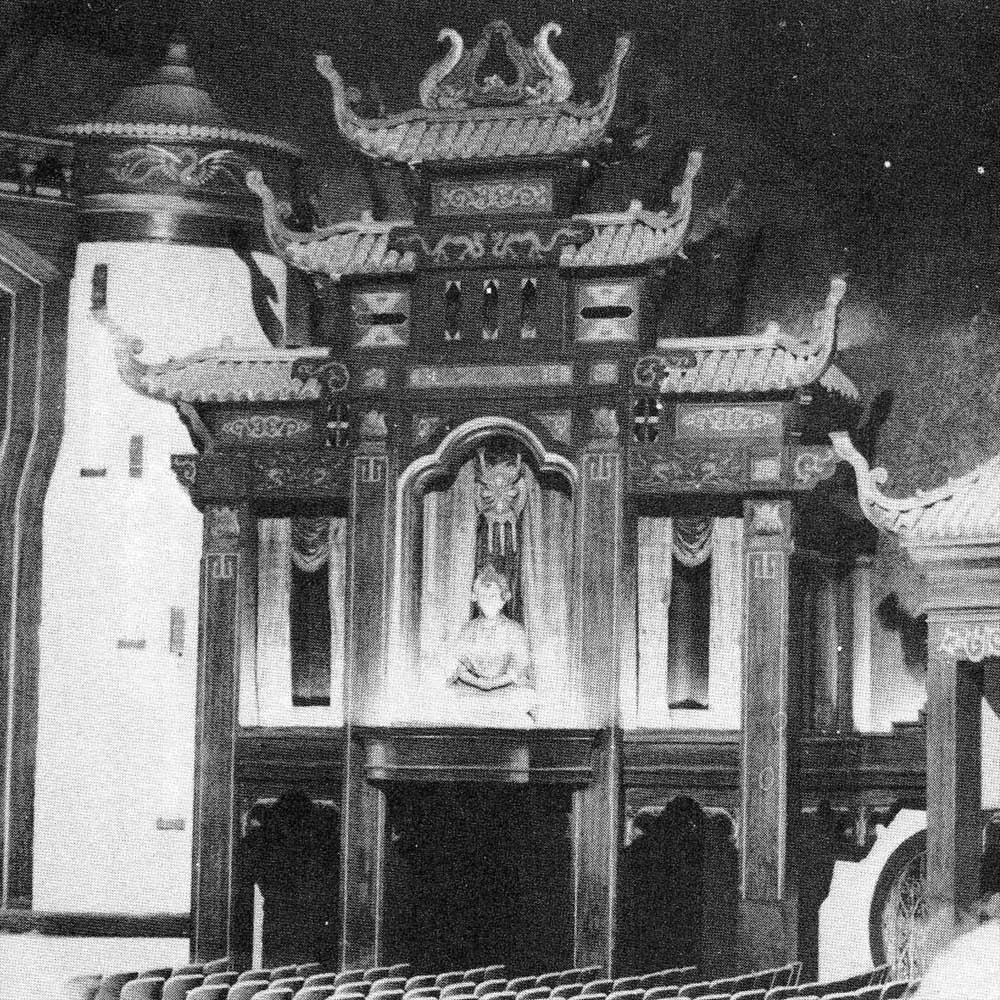

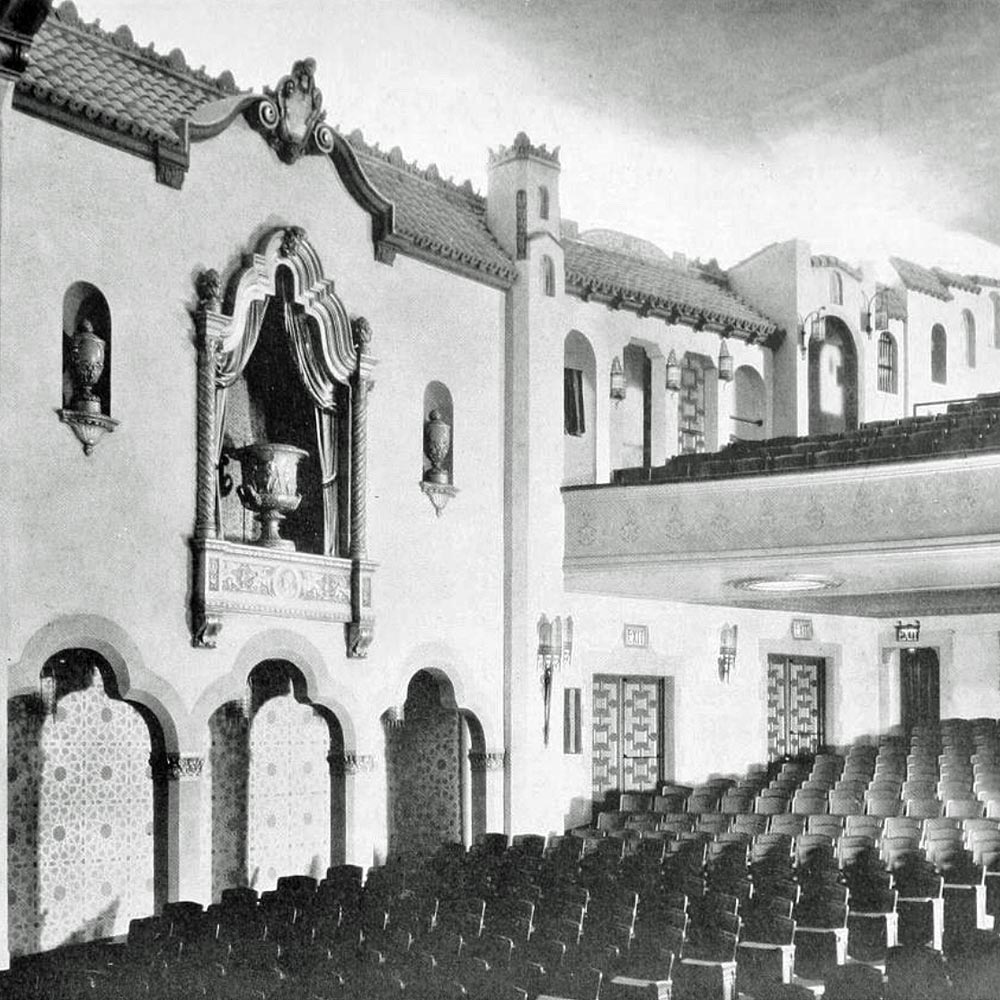

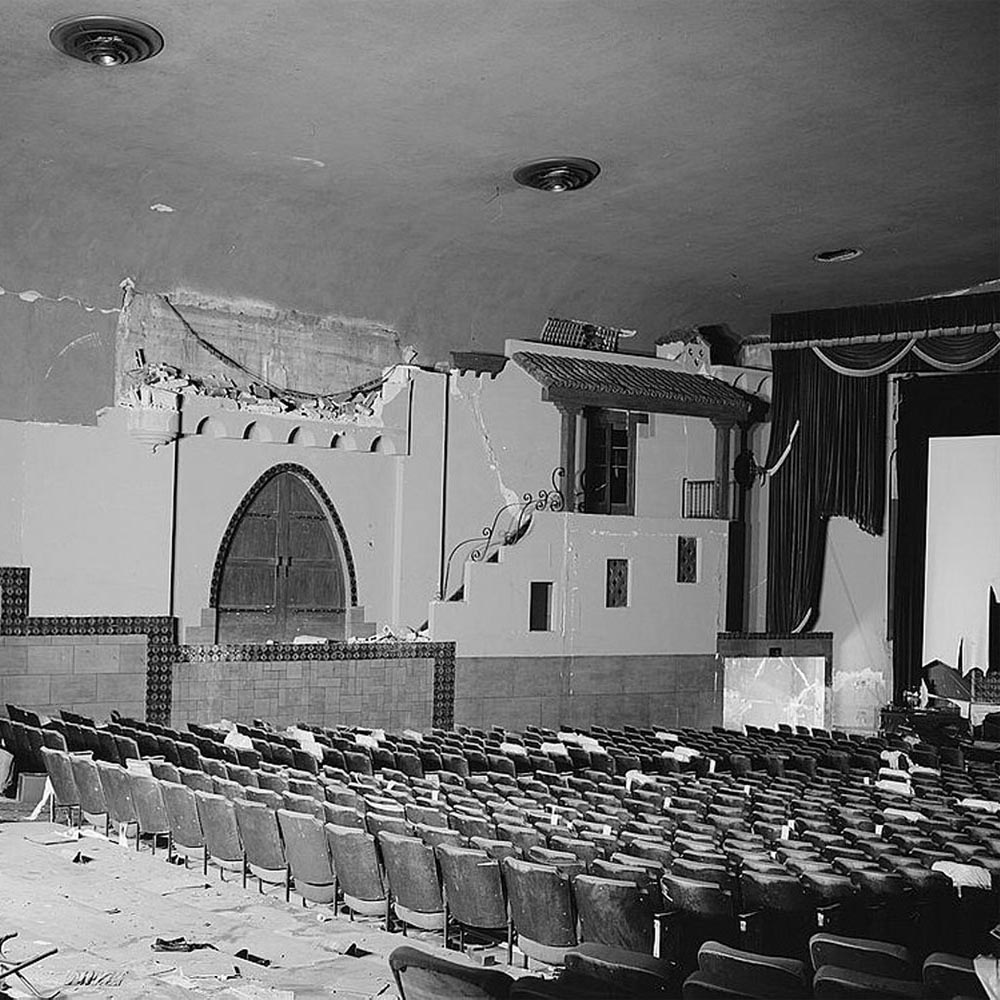

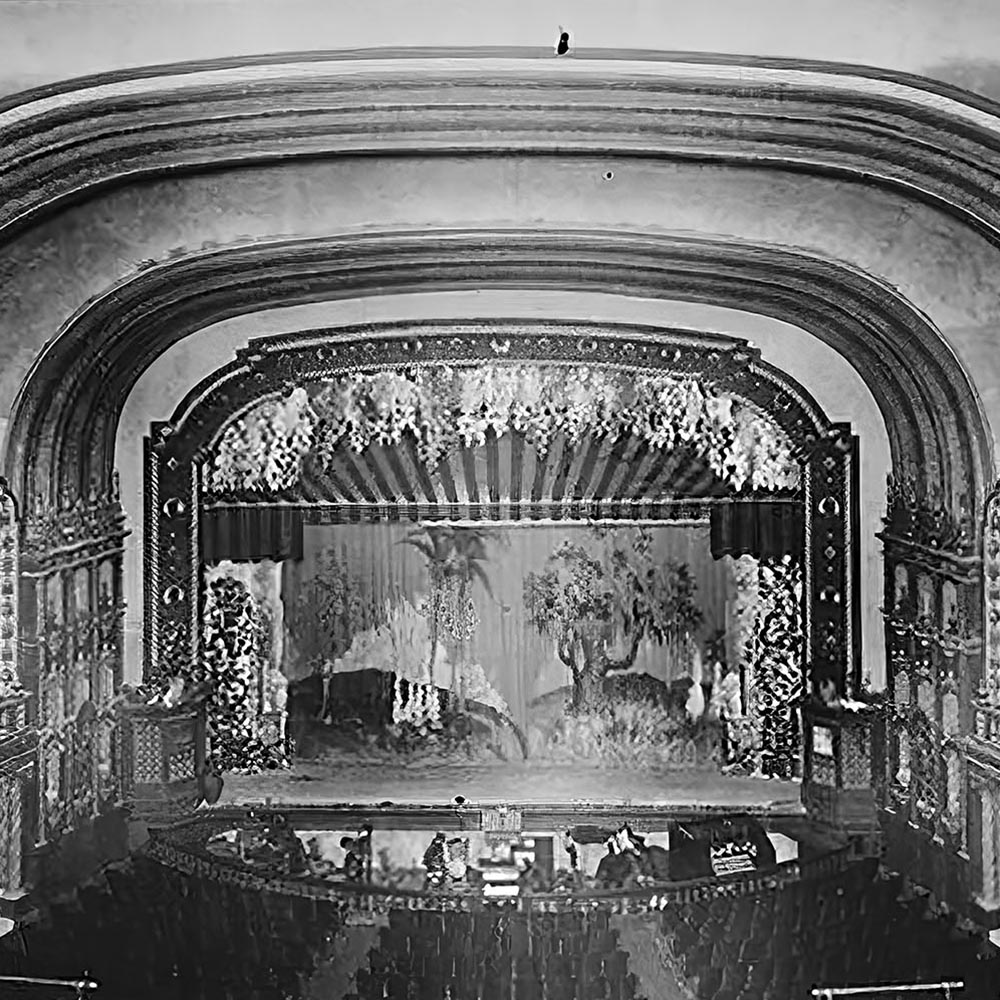

Eberson’s second Proto-Atmospheric theatre was the Indiana Theatre in Terre Haute, Indiana (opened January 1922), designed in a Moorish style featuring false balconies on the sidewalls with the organ grilles designed to look like backlit windows. The theatre design was developing into something which made it feel like the audience was sitting inside a village or community.

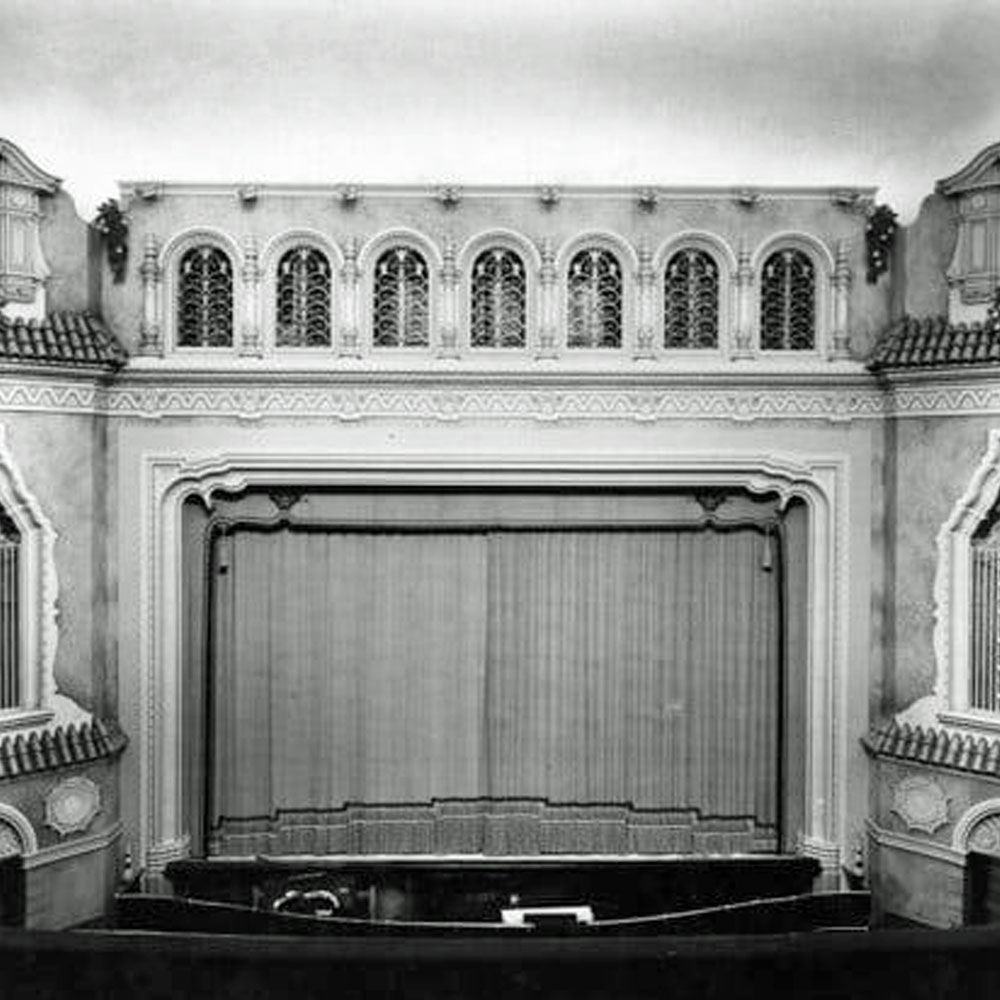

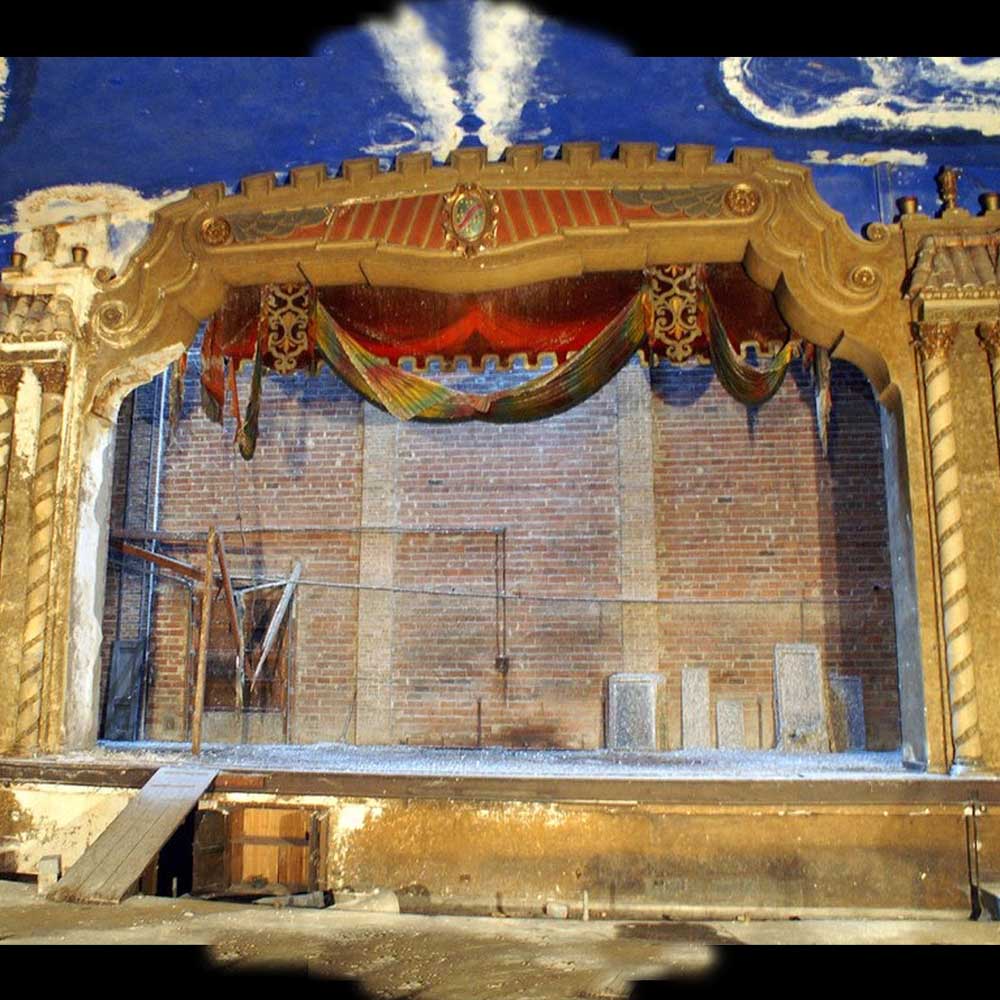

Eberson’s third and final Proto-Atmospheric theatre was the Orpheum Theatre in Wichita, Kansas (opened September 1922). While still a symmetrical auditorium design, it features statuary, niches, and window-like openings which would go on to become staple features of Eberson’s Atmospherics theatres. Notably the theatre also features a smooth blue-sky ceiling bordered by faux tilework roofs in the balcony combined with cove lighting. The ceiling currently contains stars, and if these are original this is hugely significant and adds significant strength to the theory of the theatre being one of Eberson’s Proto-Atmospheric designs.

Eberson’s first self-proclaimed Atmospheric theatre, the Majestic in Houston, garnered much attention with the press noting:

“Revolutionary developments in theatre design have been few since the beginning. Unquestionably the most innovational is the Majestic, Houston, Texas, designed by Architect John Eberson of Chicago.”

Everyone agreed, and the movie and theatre-going public flocked toward this new escape into exoticism. Theatre owners loved the lower cost and faster time to build, Eberson had no end of commissions to take up, and thus the fascination with Atmospheric Theatres was born!

Eberson was a showman; a showman whose designs glorified romantic architecture. His self-proclaimed mission was “to build new dream worlds for the disillusioned”. His legacy of historic Atmospheric theatres, largely in the United States, surely proves that he achieved that goal.

In June 1926, industry publication Motion Picture News printed an interview with Eberson as interest in Atmospheric theatres was taking hold of the movie-going audience and theatre managers alike. You can read a web-friendly version of the article, complete with color sketches by Eberson and photos of some early Atmospheric theatres, by clicking on the banner below:

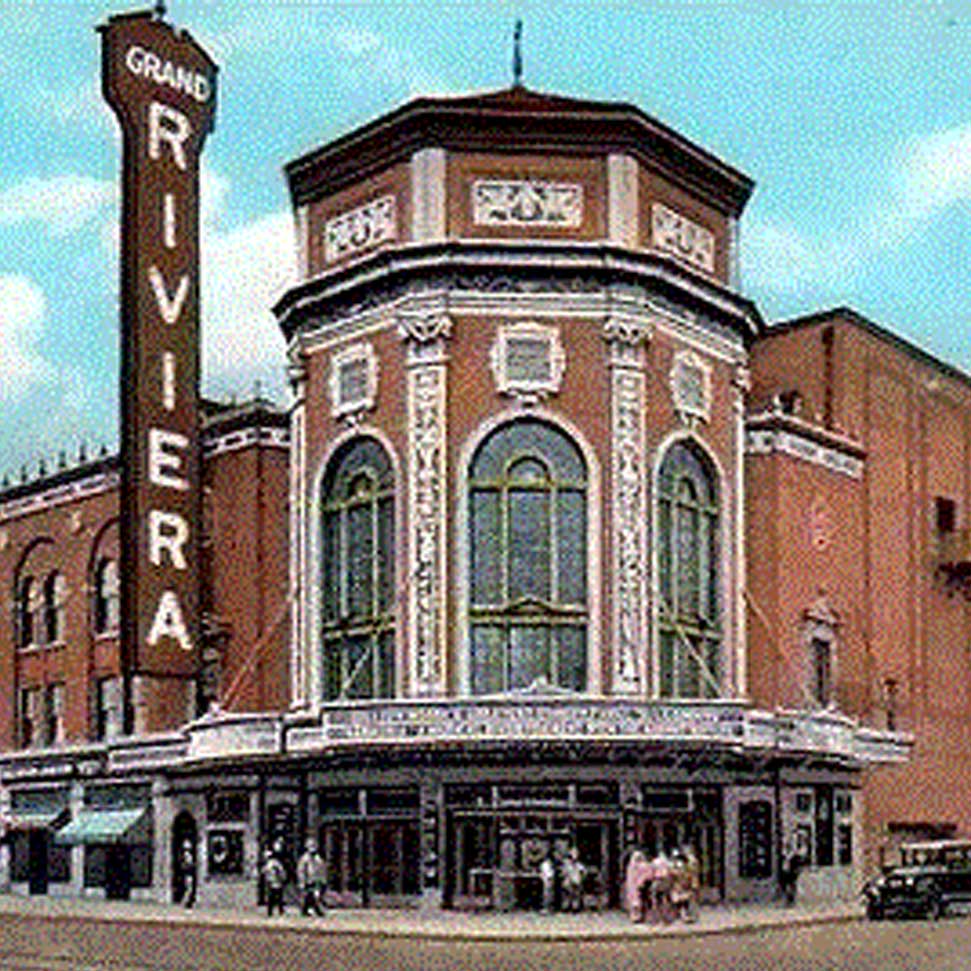

In late 1926 the Exhibitors Herald reported on theatre construction activity across the United States  and noted that the Atmospheric theatre type was gaining “such vogue” following the opening of the Capitol Theatre in Chicago. The style was winning favor across the country, evidenced by the-then recent openings of the Grand Riviera Theatre in Detroit, Michigan; the Palace Theatre in Gary, Indiana; and the Olympia Theatre in Miami, Florida (misspelled in the article as the Olympic). It was noted that the first Atmospheric theatre in New York was already planned. This would go on to open in October 1927 as the Universal Theatre in Brooklyn, New York.

and noted that the Atmospheric theatre type was gaining “such vogue” following the opening of the Capitol Theatre in Chicago. The style was winning favor across the country, evidenced by the-then recent openings of the Grand Riviera Theatre in Detroit, Michigan; the Palace Theatre in Gary, Indiana; and the Olympia Theatre in Miami, Florida (misspelled in the article as the Olympic). It was noted that the first Atmospheric theatre in New York was already planned. This would go on to open in October 1927 as the Universal Theatre in Brooklyn, New York.

The mid-1926 article was followed-up 18 months later with another major article in Motion Picture News: a second and lengthy interview with Eberson, illustrated with more color sketches from Eberson’s sketch book alongside black-and-white photographs of the increasing number of Atmospheric theatres across the United States. You can read a web-friendly version of the article, complete with all its glorious color sketches, by clicking on the banner below:

The term “Atmospheric Theatre” can be used rather loosely and at times incorrectly, so let us define the criteria used on this website for a theatre to be an Atmospheric:

Theatres which are not full Atmospherics are included here under the umbrella style of Pseudo-Atmospheric, which includes substyles such as Maverick Atmospheric, Abstract Atmospheric, and Semi-Atmospheric.

By far the most popular Atmospheric style was Spanish, accounting for 55% of all Atmospheric theatres thus far surveyed on this website.

The popularity of Spanish themes likely reflects the fact that Atmospheric theatre styles were most popular in the United States during the 1920s, at the same time as Spain was particularly alluring to Americans. Europe seemed mystical, coupled with the fact that most American theatre-goers were unlikely to have the means to visit these exotic European lands. Spanish, and to a lesser extent Italian, landscapes typified the mystic allure of Europe for Americans.

There were also a wide range of more obscure styles such as Dutch villages, Japanese tea gardens, Medieval villages, Mesoamerican temples, and even a theatre design modeled on a 16th century French chateau.

There are yet more Atmospheric styles to be found in the records of lost theatres, including examples such as underwater themes featuring Neptune and seahorses!

The popular Spanish Atmospheric style, accounting for 55% of all Atmospheric theatres thus far surveyed, can be broken down into numerous sub-styles.

While many scholars would happily argue whether a particular auditorium interior is a Spanish garden or a Spanish courtyard, Mike has researched the sub-styles listed on this website back as close to the original source as possible. When no historic direction on style is available for a particular theatre Mike has used his experience surveying Atmospheric theatre designs across the globe to decide upon a specific sub-style.

In many cases the Italian or Spanish sub-style is as quoted by the architect, however some Spanish styles are represented by how the local media interpreted the theatre at the time of reporting theatre openings. Whereas this may have been based upon interviews with the theatre’s design team Mike concedes it may in part be down to the interpretation of the reporter, and therefore potentially unreliable.

In cases where no sub-style has come to light during the research process, Mike has categorized theatres into one of the existing Spanish sub-styles. This data continues to be reviewed as additional information comes to light.

The last great Atmospheric theatre was built in the early 1940s, however the style has resurfaced at times throughout the decades.

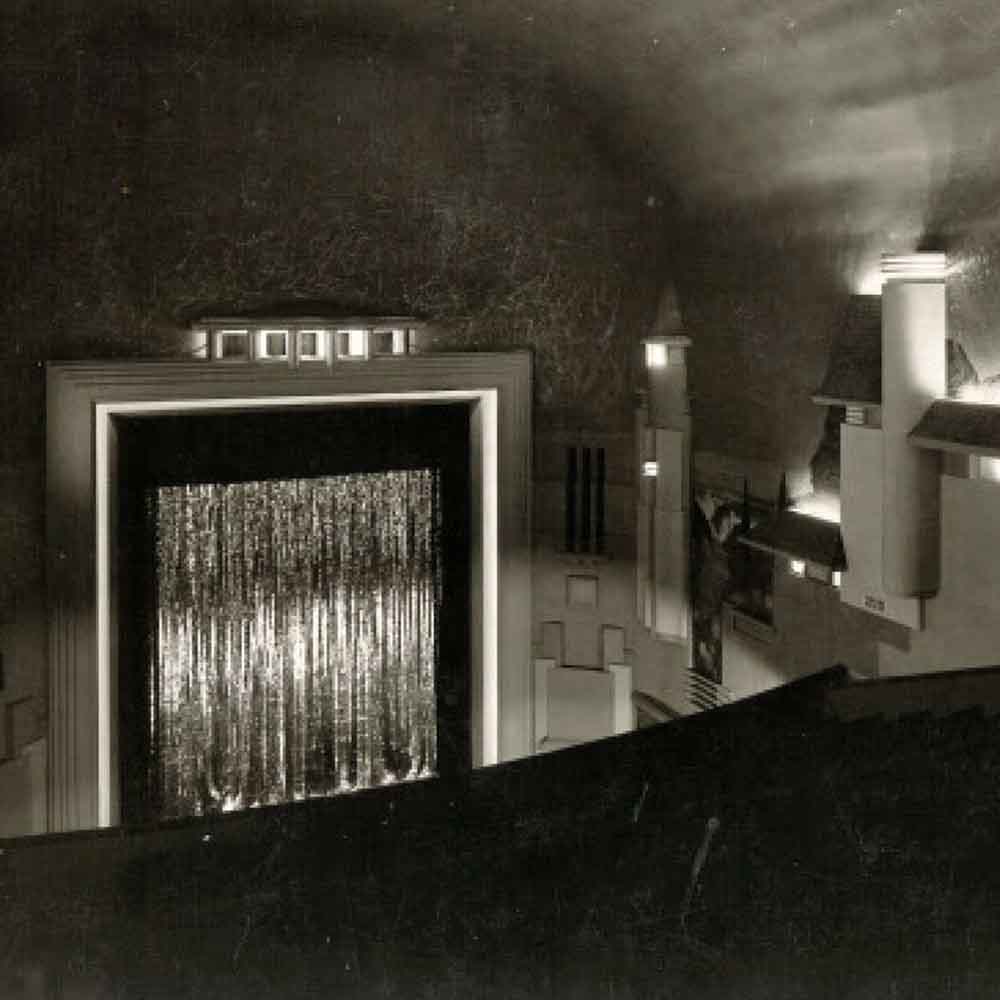

In the late 1980s Disney partnered with Pacific Theatres to renovate a single screen neighborhood theatre in Los Angeles, the Crest Theatre. Theatre designer Joseph (Joe) J. Musil headed-up the project and designed a Hollywood Revival Atmospheric interior for the renovated theatre.

The auditorium sidewalls featured stylized Hollywood and Los Angeles buildings highlighted with fluorescent paint excited by black/ultraviolet light. The auditorium ceiling was painted to look like the night sky with lights representing stars, and a “shooting star” lighting effect which was triggered just as the main feature got underway.

In the early 1990s, the MGM Grand casino opened in Las Vegas with its main lobby featuring a Wizard of Oz theme  . The huge space was capped by an Atmospheric sky ceiling dome with twinkling stars embedded in it, and images of clouds and other types of weather projected onto it.

. The huge space was capped by an Atmospheric sky ceiling dome with twinkling stars embedded in it, and images of clouds and other types of weather projected onto it.

The casino’s 1996 renovation remodeled the Atmospheric-style space into a completely different design.

The Venetian-styled shopping promenades of The Venetian Casino and Hotel in Las Vegas  , built in the late twentieth century, also borrowed from the Atmospheric theatre style and are still in place today. The style was copied by other Las Vegas casinos to afford patrons the feeling that they were shopping outside.

, built in the late twentieth century, also borrowed from the Atmospheric theatre style and are still in place today. The style was copied by other Las Vegas casinos to afford patrons the feeling that they were shopping outside.

In July 1995, additional screens opened at the Grand Lake Theatre in Oakland, California. One of these was decorated with an Egyptian theme, the sidewalls appearing as paneled vistas separated by stylized columns, and the smooth plaster ceiling being lit like a dusky sky with star lights embedded in it. The whole effect is a modern miniature version of the Egyptian Theatre in DeKalb, Illinois.

It’s interesting to analyze is the vast gulf between architects and architect firms who “had a go” at designing theatres in the Atmospheric style, and those who really embraced it.

There are 90+ extant Atmospheric theatres worldwide where the architect or architect firm designed just that single theatre in an Atmospheric style.

In contrast, John Eberson, self-proclaimed inventor of the Atmospheric theatre style, designed the vast majority of Atmospheric theatres that we’ve researched for this website.

The next most prolific architect firms to design theatres in the Atmospheric style were San Francisco-based Reid Brothers and Kansas City-based Boller Brothers.

Research on Atmospheric theatre architects is ongoing, and whereas John Eberson will always be the runaway leader it may be that runners-up will change as more research is undetaken.

By far the majority of Atmospheric theatres were built in the United States.

Our analysis of extant Atmospheric theatres shows that 76% of these are in the U.S. with the next highest concentration being in Canada, closely followed by the United Kingdom.

The statistics are hardly surprising, given the birth of the design style in the United States and the massive building boom of movie theatres in the U.S. during the mid-1920s.

Within the United States, the highest number of extant Atmospheric theatres are in the state of California. The pie chart at the right shows extant Atmospheric theatres by U.S. state.

Below is an interactive Google Map showing both extant and demolished theatres. You can interact with the map by clicking here to open the map in a new window  , or by using the map below:

, or by using the map below:

Mike has lectured extensively on Atmospheric theatre styles, and has also created an 80-minute video documentary all about the Atmospheric theatre style, its background, development, history, prolific architects, and legacy.

Unfortunately we cannot provide the documentary for free download here due to copyright but please contact Mike here  if you’re interested in seeing the video!

if you’re interested in seeing the video!

In addition to the database of Atmospheric theatres listed further down this page Mike also maintains a public Google Map of Atmospheric Theatres which is searchable by Atmospheric style plus former and current theatre names. Each theatre also includes a thumbnail photo for easy reference.

The timeline does not display well on small devices. Click here to open the timeline in a new window.

Below we present an ever-expanding list of extant and demolished atmospheric theatres from around the world. Hover over a theatre to see if it’s a link to further information – atmospheric theatre data is being added regularly (currently 87% complete).

Total number of theatres on the list: 180

Number of theatres on the list “linked” with underlying information: 156 (87%)

Theatres featured in-depth on our Historic Theatre Photos website (see links above): 34

This is a work in progress and there is much data to include such as architect information, photos, and details of current usage for those theatres not operating as originally intended. Please get in touch  if you have any data to share!

if you have any data to share!

Holland Theatre (Bellefontaine, Ohio, USA) former names: Schine’s Holland Theatre, Holland Theatre 5

Holland Theatre (Bellefontaine, Ohio, USA) former names: Schine’s Holland Theatre, Holland Theatre 5 Colosseum Theatre (Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa) [Demolished]

Colosseum Theatre (Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa) [Demolished] Egyptian Theatre (Brighton, Massachusetts, USA) [Demolished]

Egyptian Theatre (Brighton, Massachusetts, USA) [Demolished] Egyptian Theatre (DeKalb, Illinois, USA)

Egyptian Theatre (DeKalb, Illinois, USA) Odeon Streatham (London, England, UK) former name: Streatham Astoria

Odeon Streatham (London, England, UK) former name: Streatham Astoria Parkway Theater (Oakland, California, USA)

Parkway Theater (Oakland, California, USA) Peery’s Egyptian Theater (Ogden, Utah, USA)

Peery’s Egyptian Theater (Ogden, Utah, USA) Varsity Theatre (Evanston, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Varsity Theatre (Evanston, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] Paradise Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Paradise Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] Coronado Performing Arts Center (Rockford, Illinois, USA) former name: Coronado Theatre

Coronado Performing Arts Center (Rockford, Illinois, USA) former name: Coronado Theatre John P. Harris Memorial Theatre (McKeesport, Pennsylvania, USA) former names: Memorial Theatre, McKees Cinemas 1 & 2 [Demolished]

John P. Harris Memorial Theatre (McKeesport, Pennsylvania, USA) former names: Memorial Theatre, McKees Cinemas 1 & 2 [Demolished] Paramount Theatre (Abilene, Texas, USA) former names: Paramount Opry, Paramount Country Music Hall

Paramount Theatre (Abilene, Texas, USA) former names: Paramount Opry, Paramount Country Music Hall Rose Blumkin Performing Arts Center (Omaha, Nebraska, USA) former names: Riviera Theatre, Paramount Theatre, Astro Theatre

Rose Blumkin Performing Arts Center (Omaha, Nebraska, USA) former names: Riviera Theatre, Paramount Theatre, Astro Theatre Assembly Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Jersey City, New Jersey, USA) former name: Stanley Theater

Assembly Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Jersey City, New Jersey, USA) former name: Stanley Theater Capitol Theatre (Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa)

Capitol Theatre (Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa) Capitol Theatre (Flint, Michigan, USA)

Capitol Theatre (Flint, Michigan, USA) Copernicus Center (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former name: Gateway Theater

Copernicus Center (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former name: Gateway Theater Crown Uptown Theatre (Wichita, Kansas, USA) former names: Uptown Theatre, New Uptown Theatre

Crown Uptown Theatre (Wichita, Kansas, USA) former names: Uptown Theatre, New Uptown Theatre Hershey Theatre (Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA)

Hershey Theatre (Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA) Loew’s Triboro (New York, New York, USA) [Demolished]

Loew’s Triboro (New York, New York, USA) [Demolished] Paradise Theater (The Bronx, New York, USA) former names: Venetian Theatre, Loew’s Paradise

Paradise Theater (The Bronx, New York, USA) former names: Venetian Theatre, Loew’s Paradise  Paramount Theatre (Toledo, Ohio, USA) [Demolished]

Paramount Theatre (Toledo, Ohio, USA) [Demolished] Patio Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA)

Patio Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) Riviera Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former name: Grand Riviera Theatre [Demolished]

Riviera Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former name: Grand Riviera Theatre [Demolished] Saenger Theatre (New Orleans, Louisiana, USA)

Saenger Theatre (New Orleans, Louisiana, USA) Savoy Cinema (Dublin, Leinster, Ireland)

Savoy Cinema (Dublin, Leinster, Ireland) State Theater (Stoughton, Massachusetts, USA)

State Theater (Stoughton, Massachusetts, USA) Ambassador’s Theatre (Perth, Western Australia, Australia) [Demolished]

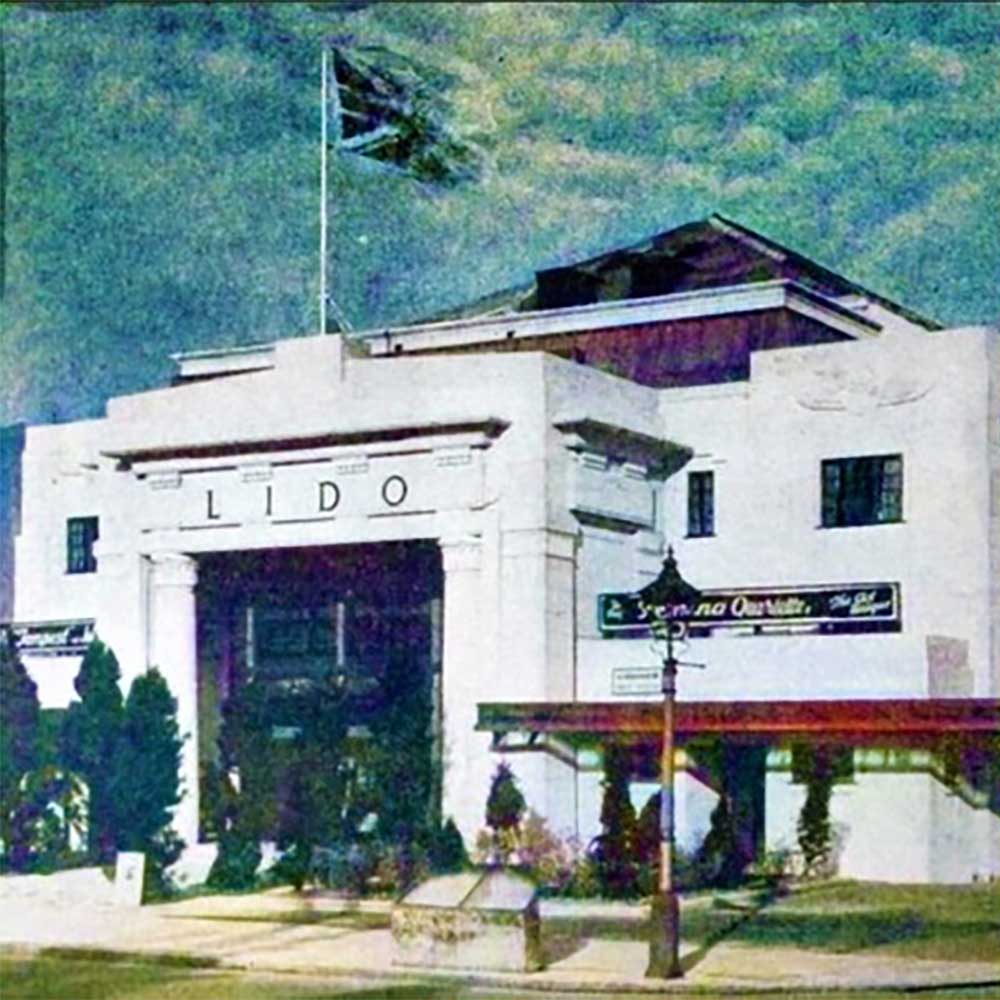

Ambassador’s Theatre (Perth, Western Australia, Australia) [Demolished] Cannon Golders Green (London, England, UK) former names: Lido Picture House, ABC [Demolished]

Cannon Golders Green (London, England, UK) former names: Lido Picture House, ABC [Demolished] Capitol Theatre (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia)

Capitol Theatre (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) Capitol Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Capitol Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] Forum Melbourne (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) former name: State Theatre

Forum Melbourne (Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) former name: State Theatre Fountain Square Theatre (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA)

Fountain Square Theatre (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) Loew’s 46th Street Theatre (New York - Brooklyn, New York, USA) former name: Universal Theatre [Demolished]

Loew’s 46th Street Theatre (New York - Brooklyn, New York, USA) former name: Universal Theatre [Demolished] Majestic Theatre (Houston, Texas, USA) [Demolished]

Majestic Theatre (Houston, Texas, USA) [Demolished] Majestic Theatre (Staines, England, UK) [Demolished]

Majestic Theatre (Staines, England, UK) [Demolished] National Theatre (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) [Demolished]

National Theatre (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) [Demolished] O2 Academy Brixton (London, England, UK) former names: Brixton Astoria, Astoria Variety Cinema, Sundown Centre, Carling Academy Brixton

O2 Academy Brixton (London, England, UK) former names: Brixton Astoria, Astoria Variety Cinema, Sundown Centre, Carling Academy Brixton Odeon Theatre (Goulburn, New South Wales, Australia) former name: Empire Theatre [Demolished]

Odeon Theatre (Goulburn, New South Wales, Australia) former name: Empire Theatre [Demolished] Uptown Theater (Kansas City, Missouri, USA)

Uptown Theater (Kansas City, Missouri, USA) Venetian Theatre (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) [Demolished]

Venetian Theatre (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) [Demolished] Polk Theatre (Lakeland, Florida, USA) former name: Melton Theatre

Polk Theatre (Lakeland, Florida, USA) former name: Melton Theatre Uptown Theatre (Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA) former name: Oxford Theatre [Demolished]

Uptown Theatre (Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA) former name: Oxford Theatre [Demolished] Aztec Theatre (San Antonio, Texas, USA)

Aztec Theatre (San Antonio, Texas, USA) Teatro Sierra Maestra (Havana, Havana, Cuba) former name: Teatro Lutgardita

Teatro Sierra Maestra (Havana, Havana, Cuba) former name: Teatro Lutgardita , and is the most recent Atmospheric theatre to have been commissioned across the globe.

, and is the most recent Atmospheric theatre to have been commissioned across the globe. Hollywood Theater (Dormont, Pennsylvania, USA)

Hollywood Theater (Dormont, Pennsylvania, USA) Keith-Albee Performing Arts Center (Huntington, West Virginia, USA) former name: Keith-Albee Theatre

Keith-Albee Performing Arts Center (Huntington, West Virginia, USA) former name: Keith-Albee Theatre Alhambra Cinema (Birmingham, England, UK) [Demolished]

Alhambra Cinema (Birmingham, England, UK) [Demolished] Avalon Regal Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former names: Avalon Theater, Miracle Temple Church, New Regal Theater

Avalon Regal Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former names: Avalon Theater, Miracle Temple Church, New Regal Theater Cine Rex (Ghent, East Flanders, Belgium)

Cine Rex (Ghent, East Flanders, Belgium) Cinema Rex (Bordeaux, New Aquitania, France) [Demolished]

Cinema Rex (Bordeaux, New Aquitania, France) [Demolished] Missouri Theater (St. Joseph, Missouri, USA)

Missouri Theater (St. Joseph, Missouri, USA) Oriental Theater (Denver, Colorado, USA)

Oriental Theater (Denver, Colorado, USA) Paradise Center for the Arts (Faribault, Minnesota, USA) former names: Granada Theater, Paramount Theatre, Paradise Theatre, Faribault Art Center

Paradise Center for the Arts (Faribault, Minnesota, USA) former names: Granada Theater, Paramount Theatre, Paradise Theatre, Faribault Art Center Rialto Cinema (Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand)

Rialto Cinema (Dunedin, Otago, New Zealand) Teatro de la Ciudad (Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico) former names: Teatro Betancourt, El Centenario, Cine Colonial

Teatro de la Ciudad (Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico) former names: Teatro Betancourt, El Centenario, Cine Colonial Cine Elizondo (Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico) [Demolished]

Cine Elizondo (Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico) [Demolished] Cinemex Real (Mexico City, Mexico City, Mexico) former name: Palacio Chino

Cinemex Real (Mexico City, Mexico City, Mexico) former name: Palacio Chino Oriental Theatre (Boston, Massachusetts, USA)

Oriental Theatre (Boston, Massachusetts, USA) Pekin Theatre (Pekin, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Pekin Theatre (Pekin, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] Civic Theatre (Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand)

Civic Theatre (Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand) Oriental Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former names: Oriental Theatre, RKO Downtown, Downtown Theatre [Demolished]

Oriental Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former names: Oriental Theatre, RKO Downtown, Downtown Theatre [Demolished] Visalia Fox Theatre (Visalia, California, USA) former name: Fox Theatre

Visalia Fox Theatre (Visalia, California, USA) former name: Fox Theatre Fox Theatre (Atlanta, Georgia, USA)

Fox Theatre (Atlanta, Georgia, USA) Redford Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former name: Kunsky-Redford Theatre

Redford Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former name: Kunsky-Redford Theatre Loew’s 72nd Street Theatre (New York - Manhattan, New York, USA) [Demolished]

Loew’s 72nd Street Theatre (New York - Manhattan, New York, USA) [Demolished] Indiana Theatre (Terre Haute, Indiana, USA) former name: Indiana Theatre Event Center

Indiana Theatre (Terre Haute, Indiana, USA) former name: Indiana Theatre Event Center Majestic Theatre (Dallas, Texas, USA)

Majestic Theatre (Dallas, Texas, USA) Orpheum Theatre (Wichita, Kansas, USA)

Orpheum Theatre (Wichita, Kansas, USA) Palace Theatre (Flint, Michigan, USA) [Demolished]

Palace Theatre (Flint, Michigan, USA) [Demolished] Avalon Theatre (Avalon, California, USA)

Avalon Theatre (Avalon, California, USA) Kelvin Cinema (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) [Demolished]

Kelvin Cinema (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) [Demolished] Orient Cinema (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) [Demolished]

Orient Cinema (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) [Demolished] Nimoy Theater (Los Angeles, California, USA) former names: UCLAN Theatre, Crest Theatre, Loew’s Crest, Metro Theatre, Pacific’s Crest, Crest Westwood

Nimoy Theater (Los Angeles, California, USA) former names: UCLAN Theatre, Crest Theatre, Loew’s Crest, Metro Theatre, Pacific’s Crest, Crest Westwood Avenue Theatre (London, England, UK) former names: Spanish City Cinema, Odeon Theatre Northfields, Coronet Cinema

Avenue Theatre (London, England, UK) former names: Spanish City Cinema, Odeon Theatre Northfields, Coronet Cinema New Victoria Cinema (Edinburgh, Scotland, UK) former name: Odeon Edinburgh

New Victoria Cinema (Edinburgh, Scotland, UK) former name: Odeon Edinburgh Patricia Theatre (Powell River, British Columbia, Canada)

Patricia Theatre (Powell River, British Columbia, Canada) Poncan Theatre (Ponca City, Oklahoma, USA)

Poncan Theatre (Ponca City, Oklahoma, USA) Southtown Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Southtown Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] State Theatre (Ithaca, New York, USA) former name: State Theater

State Theatre (Ithaca, New York, USA) former name: State Theater Boulevard Picture House (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) former name: Vogue Cinema [Demolished]

Boulevard Picture House (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) former name: Vogue Cinema [Demolished] Akron Civic Theatre (Akron, Ohio, USA) former name: Loew’s Akron

Akron Civic Theatre (Akron, Ohio, USA) former name: Loew’s Akron Arlington Theatre (Santa Barbara, California, USA)

Arlington Theatre (Santa Barbara, California, USA) Spanish Hall, Blackpool Winter Gardens (Blackpool, England, UK) former names: Spanish Congress Hall, Spanish Courtyard

Spanish Hall, Blackpool Winter Gardens (Blackpool, England, UK) former names: Spanish Congress Hall, Spanish Courtyard Avalon Atmospheric Theater (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Bay View Theater, Avalon Theater, Garden Theater

Avalon Atmospheric Theater (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Bay View Theater, Avalon Theater, Garden Theater Bama Theatre (Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA)

Bama Theatre (Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA) Campbeltown Picture House (Campbeltown, Scotland, UK)

Campbeltown Picture House (Campbeltown, Scotland, UK) Lido Theatre (The Pas, Manitoba, Canada) [Demolished]

Lido Theatre (The Pas, Manitoba, Canada) [Demolished] Majestic Theatre (Nampa, Idaho, USA) former names: Nampa Opera House, Nampa Theatre [Demolished]

Majestic Theatre (Nampa, Idaho, USA) former names: Nampa Opera House, Nampa Theatre [Demolished] Mayfair Theatre (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada)

Mayfair Theatre (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) Music Box Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA)

Music Box Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) Ritz Theatre (Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) [Demolished]

Ritz Theatre (Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA) [Demolished] Tampa Theatre (Tampa, Florida, USA)

Tampa Theatre (Tampa, Florida, USA) Arcadia Theatre (Dallas, Texas, USA) [Demolished]

Arcadia Theatre (Dallas, Texas, USA) [Demolished] Carpenter Theatre (Richmond, Virginia, USA) former name: Loew’s Theatre

Carpenter Theatre (Richmond, Virginia, USA) former name: Loew’s Theatre Russell Theatre (Maysville, Kentucky, USA)

Russell Theatre (Maysville, Kentucky, USA) Uptown Theatre (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada)

Uptown Theatre (Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada) Louisville Palace Theatre (Louisville, Kentucky, USA) former name: Loew’s and United Artists’ State Theater

Louisville Palace Theatre (Louisville, Kentucky, USA) former name: Loew’s and United Artists’ State Theater RKO Keith’s Theater (New York - Queens, New York, USA) [Demolished]

RKO Keith’s Theater (New York - Queens, New York, USA) [Demolished] Smith Opera House (Geneva, New York, USA) former names: Geneva Theatre, Smith’s Opera House

Smith Opera House (Geneva, New York, USA) former names: Geneva Theatre, Smith’s Opera House Annex Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former name: Riviera Annex Theatre [Demolished]

Annex Theatre (Detroit, Michigan, USA) former name: Riviera Annex Theatre [Demolished] El Raton Theatre (Raton, New Mexico, USA)

El Raton Theatre (Raton, New Mexico, USA) Elmwood Theatre (Elmhurst, New York, USA) former names: Queensboro Theatre, Loews Cineplex Elmwood

Elmwood Theatre (Elmhurst, New York, USA) former names: Queensboro Theatre, Loews Cineplex Elmwood Golden State Theatre (Monterey, California, USA) former name: State Theatre

Golden State Theatre (Monterey, California, USA) former name: State Theatre Kenosha Theatre (Kenosha, Wisconsin, USA)

Kenosha Theatre (Kenosha, Wisconsin, USA) Ritz Cinema (Cambuslang, Scotland, UK) [Demolished]

Ritz Cinema (Cambuslang, Scotland, UK) [Demolished] State Theatre (Lexington, Kentucky, USA)

State Theatre (Lexington, Kentucky, USA) Alberta Rose Theatre (Portland, Oregon, USA) former name: Alameda Theatre

Alberta Rose Theatre (Portland, Oregon, USA) former name: Alameda Theatre Alhambra Theatre (Hopkinsville, Kentucky, USA)

Alhambra Theatre (Hopkinsville, Kentucky, USA) Avon Theatre (Medford, Wisconsin, USA)

Avon Theatre (Medford, Wisconsin, USA) Barrymore Theatre (Madison, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Eastwood Theater, Cinema Theater

Barrymore Theatre (Madison, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Eastwood Theater, Cinema Theater Canton Palace Theatre (Canton, Ohio, USA)

Canton Palace Theatre (Canton, Ohio, USA) Capitol Theatre (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) [Demolished]

Capitol Theatre (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) [Demolished] Cineteca Alameda (San Luis Potosi, San Luis Potosi, Mexico) former name: Cine Teatro Alameda

Cineteca Alameda (San Luis Potosi, San Luis Potosi, Mexico) former name: Cine Teatro Alameda Emanuel Evangelist Temple (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) former name: Zenith Theatre

Emanuel Evangelist Temple (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) former name: Zenith Theatre Fox Theater Bakersfield (Bakersfield, California, USA) former name: Fox Theatre

Fox Theater Bakersfield (Bakersfield, California, USA) former name: Fox Theatre Fox Theatre (Redwood City, California, USA) former name: New Sequoia Theatre

Fox Theatre (Redwood City, California, USA) former name: New Sequoia Theatre Garden Theatre (Winter Garden, Florida, USA) former name: Winter Garden Theater

Garden Theatre (Winter Garden, Florida, USA) former name: Winter Garden Theater Granada Theatre (Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada)

Granada Theatre (Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada) Granada Theatre (Cleveland, Ohio, USA) former name: Loew’s Granada Theatre [Demolished]

Granada Theatre (Cleveland, Ohio, USA) former name: Loew’s Granada Theatre [Demolished] Hanford Fox Theatre (Hanford, California, USA) former name: Hanford Theatre

Hanford Fox Theatre (Hanford, California, USA) former name: Hanford Theatre Merced Theatre (Merced, California, USA) former names: Elite Theatre, Strand Theatre, Rio Theatre, United Artists Merced Movies 4

Merced Theatre (Merced, California, USA) former names: Elite Theatre, Strand Theatre, Rio Theatre, United Artists Merced Movies 4 Midwest Theatre (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA) [Demolished]

Midwest Theatre (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA) [Demolished] Monkland Theatre (Montreal, Quebec, Canada)

Monkland Theatre (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) Newark Gospel Tabernacle (Newark, New Jersey, USA) former name: Stanley Theatre

Newark Gospel Tabernacle (Newark, New Jersey, USA) former name: Stanley Theatre Odeon Richmond (Richmond, England, UK) former names: Richmond Kinema, Premier Cinema

Odeon Richmond (Richmond, England, UK) former names: Richmond Kinema, Premier Cinema Palace Theatre (Marion, Ohio, USA)

Palace Theatre (Marion, Ohio, USA) Paramount Theatre (Anderson, Indiana, USA)

Paramount Theatre (Anderson, Indiana, USA) Paramount Theatre (Long Branch, New Jersey, USA) former name: Broadway Theatre [Demolished]

Paramount Theatre (Long Branch, New Jersey, USA) former name: Broadway Theatre [Demolished] Patio Theatre (Freeport, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Patio Theatre (Freeport, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] Plaza Theatre (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia)

Plaza Theatre (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia) Plaza Theatre (Glasgow, Kentucky, USA)

Plaza Theatre (Glasgow, Kentucky, USA) Ramova Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former name: Ramova Theater

Ramova Theatre (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former name: Ramova Theater Ritz Theatre (Corpus Christi, Texas, USA) former name: Ritz Music Hall

Ritz Theatre (Corpus Christi, Texas, USA) former name: Ritz Music Hall Ritz Ybor (Tampa, Florida, USA) former names: Rivoli Theatre, Ritz Theatre, Masquerade nightclub

Ritz Ybor (Tampa, Florida, USA) former names: Rivoli Theatre, Ritz Theatre, Masquerade nightclub Rivoli Theatre & Pizzeria (La Crosse, Wisconsin, USA) former name: Rivoli Theatre

Rivoli Theatre & Pizzeria (La Crosse, Wisconsin, USA) former name: Rivoli Theatre Runnymede Theatre (Toronto, Ontario, Canada)

Runnymede Theatre (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) State Theatre (Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA)

State Theatre (Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA) The State Room (South San Francisco, California, USA) former name: State Theater

The State Room (South San Francisco, California, USA) former name: State Theater Théâtre Denise-Pelletier (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) former name: Granada Theatre

Théâtre Denise-Pelletier (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) former name: Granada Theatre Tivoli Theatre (Spencer, Indiana, USA)

Tivoli Theatre (Spencer, Indiana, USA) Toledo Picture House (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) former names: Toledo Cinema, ABC Muirend [Demolished]

Toledo Picture House (Glasgow, Scotland, UK) former names: Toledo Cinema, ABC Muirend [Demolished] Uptown Theater (San Francisco, California, USA) former names: New Alcazar Theatre, Republic Theatre, Sutter Theatre, Lloyd Downton’s Uptown [Demolished]

Uptown Theater (San Francisco, California, USA) former names: New Alcazar Theatre, Republic Theatre, Sutter Theatre, Lloyd Downton’s Uptown [Demolished] Venetian Theatre (Racine, Wisconsin, USA) former name: Racine Theatre [Demolished]

Venetian Theatre (Racine, Wisconsin, USA) former name: Racine Theatre [Demolished] Warner Theatre (Atlantic City, New Jersey, USA) former names: Warner’s Embassy Theatre, Warren Theatre [Demolished]

Warner Theatre (Atlantic City, New Jersey, USA) former names: Warner’s Embassy Theatre, Warren Theatre [Demolished] Whittier Theatre (Whittier, California, USA) former names: McNees Theatre, Warner Bros. Whittier, Bruen’s Whittier [Demolished]

Whittier Theatre (Whittier, California, USA) former names: McNees Theatre, Warner Bros. Whittier, Bruen’s Whittier [Demolished] Le Grand Rex (Paris, Île-de-France, France)

Le Grand Rex (Paris, Île-de-France, France) 7th Street Theatre (Hoquiam, Washington, USA) former name: Seventh Street Theatre

7th Street Theatre (Hoquiam, Washington, USA) former name: Seventh Street Theatre Capitol Theater (Rockford, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Capitol Theater (Rockford, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] Cinemax Cinema (Edgware, England, UK) former names: Ritz Cinema, ABC, Cannon, Belle-Vue Cinema [Demolished]

Cinemax Cinema (Edgware, England, UK) former names: Ritz Cinema, ABC, Cannon, Belle-Vue Cinema [Demolished] Daly City Theatre (Daly City, California, USA) [Demolished]

Daly City Theatre (Daly City, California, USA) [Demolished] DuPage Theater (Lombard, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

DuPage Theater (Lombard, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] El Patio Theatre (Tyrone, Pennsylvania, USA) [Demolished]

El Patio Theatre (Tyrone, Pennsylvania, USA) [Demolished] Granada Theater (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) former name: Suburban World Theatre

Granada Theater (Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) former name: Suburban World Theatre Lensic Performing Arts Center (Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA) former name: Lensic Theatre

Lensic Performing Arts Center (Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA) former name: Lensic Theatre Olympia Theater (Miami, Florida, USA)

Olympia Theater (Miami, Florida, USA) Orpheum Theatre (Phoenix, Arizona, USA)

Orpheum Theatre (Phoenix, Arizona, USA) Palace Theatre (Gary, Indiana, USA) former names: Star Palace Theatre, Star Academy of Performing Arts and Sciences [Demolished]

Palace Theatre (Gary, Indiana, USA) former names: Star Palace Theatre, Star Academy of Performing Arts and Sciences [Demolished] Plaza Theatre (El Paso, Texas, USA)

Plaza Theatre (El Paso, Texas, USA) Plaza Theatre (Schenectady, New York, USA) former name: RKO Plaza Theatre [Demolished]

Plaza Theatre (Schenectady, New York, USA) former name: RKO Plaza Theatre [Demolished] Stefanie H. Weill Center for the Performing Arts (Sheboygan, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Sheboygan Theatre, Plaza 8 Sheboygan Cinemas I & II

Stefanie H. Weill Center for the Performing Arts (Sheboygan, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Sheboygan Theatre, Plaza 8 Sheboygan Cinemas I & II Tabernacle of Prayer for All People (Jamaica, New York, USA) former names: Loew’s Valencia, Valencia Theatre

Tabernacle of Prayer for All People (Jamaica, New York, USA) former names: Loew’s Valencia, Valencia Theatre Texas Theatre (San Angelo, Texas, USA)

Texas Theatre (San Angelo, Texas, USA) Warner Hollywood (Hollywood, California, USA) former name: Hollywood Pacific

Warner Hollywood (Hollywood, California, USA) former name: Hollywood Pacific Majestic Theatre (San Antonio, Texas, USA)

Majestic Theatre (San Antonio, Texas, USA) Meyer Theatre (Green Bay, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Fox Theatre, Bay Theatre, Bay 3

Meyer Theatre (Green Bay, Wisconsin, USA) former names: Fox Theatre, Bay Theatre, Bay 3 Paramount Theatre (Austin, Minnesota, USA)

Paramount Theatre (Austin, Minnesota, USA) Roxy Theatre (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) former name: Towne Cinema

Roxy Theatre (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada) former name: Towne Cinema Byline Bank Aragon Ballroom (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former name: Aragon Ballroom

Byline Bank Aragon Ballroom (Chicago, Illinois, USA) former name: Aragon Ballroom Indiana Roof Ballroom (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) former name: Indiana Ballroom

Indiana Roof Ballroom (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA) former name: Indiana Ballroom Palace Theater (Oakland, California, USA)

Palace Theater (Oakland, California, USA) Plaza Theatre (Palm Springs, California, USA)

Plaza Theatre (Palm Springs, California, USA) Rainbow Theatre (London, England, UK) former name: Finsbury Park Astoria

Rainbow Theatre (London, England, UK) former name: Finsbury Park Astoria Nortown Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished]

Nortown Theater (Chicago, Illinois, USA) [Demolished] with any concerns. Photos displayed in this page may be subject to copyright; refer to our Copyright Fair Use Statement regarding our use of copyrighted media.

with any concerns. Photos displayed in this page may be subject to copyright; refer to our Copyright Fair Use Statement regarding our use of copyrighted media.Photographs copyright © 2002-2026 Mike Hume / Historic Theatre Photos unless otherwise noted.

Text copyright © 2017-2026 Mike Hume / Historic Theatre Photos.

For photograph licensing and/or re-use contact us here  . See our Sharing Guidelines here

. See our Sharing Guidelines here  .

.

| Follow Mike Hume’s Historic Theatre Photography: |  |

|